What the Fed and “Too Late” Powell Can Learn From FDR’s Supreme Court

The switch in time that saved nine

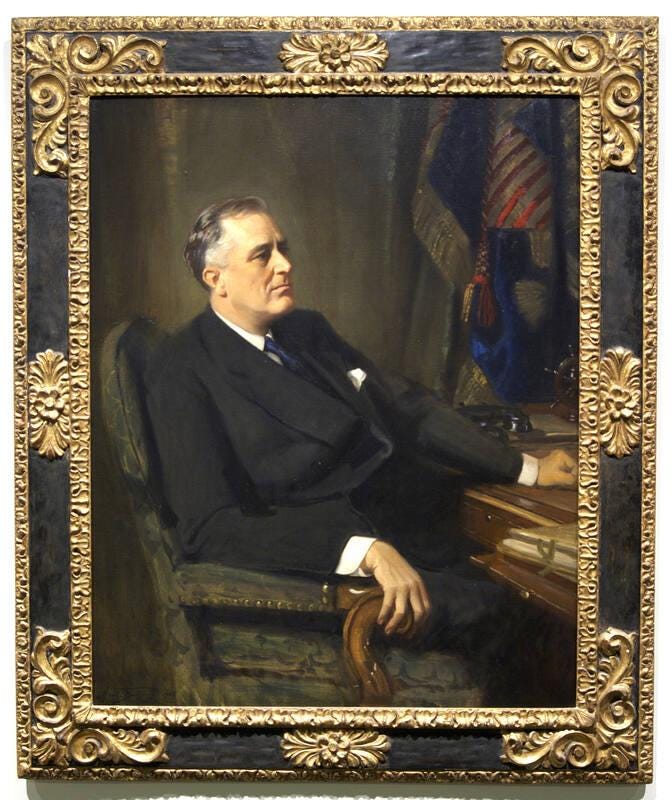

President Trump is such a fan of Franklin Delano Roosevelt that he has portraits of FDR up in both the Oval Office and the Cabinet Room. “A four-termer,” Trump has called him, with some admiration and perhaps even just a touch of envy, “an amazing man.” (If William Leuchtenburg, who died in January 2025 at age 102, were alive, he’d doubtless be updating his classic “In the Shadow of FDR” book with some additional pages for a new edition interpreting Trump in the light of FDR, as he did for so many previous presidents).

Trump’s dramatic public clash with the Federal Reserve—whose chairman, Jerome “Too Slow” Powell, accused Trump in a Sunday night video of “threats,” “intimidation,” and “political pressure”—has certain parallels to Roosevelt’s court-packing scheme.

The Federal Judicial Center has a concise summary of that plan for those who don’t recall the details from civics or U.S. history: “After winning the 1936 presidential election in a landslide, Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed a bill to expand the membership of the Supreme Court. The law would have added one justice to the Court for each justice over the age of 70, with a maximum of six additional justices. Roosevelt’s motive was clear – to shape the ideological balance of the Court so that it would cease striking down his New Deal legislation. As a result, the plan was widely and vehemently criticized. The law was never enacted by Congress, and Roosevelt lost a great deal of political support for having proposed it. Shortly after the president made the plan public, however, the Court upheld several government regulations of the type it had formerly found unconstitutional. In National Labor Relations Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel Corporation, for example, the Court upheld the right of the federal government to regulate labor-management relations pursuant to the National Labor Relations Act of 1935. Many have attributed this and similar decisions to a politically motivated change of heart on the part of Justice Owen Roberts, often referred to as ‘the switch in time that saved nine.’ Some legal scholars have rejected this narrative, however, asserting that Roberts’ 1937 decisions were not motivated by Roosevelt’s proposal and can instead be reconciled with his prior jurisprudence.”

FDR versus the Supreme Court is not precisely the same as Trump versus Powell and the Fed. The Supreme Court is in the text of the Constitution, while the Federal Reserve is not. Roosevelt, in my view, wanted to push the court in the wrong direction of greater executive branch and federal power, while Trump wants to push the Fed in, in my view, the right direction of lower interest rates and better overall management, including restoring the intellectual diversity and vitality that once characterized the regional Fed banks.

But in the sense of a president seeking to use political power to overcome an unelected obstacle that seemed unaccountable, obstinate, and oppositional, the parallel is there.

There’s also a parallel in the sense of Congress—the branch in Article I of the Constitution—looking askance at unbridled executive power. In FDR’s case, the Senate rejected the court-packing plan by a 70-20 vote. In Trump’s case, the Republican chair of the House Financial Services Committee, French Hill, is choosing to side with Powell against Trump, as did Senator Tillis of North Carolina, a Republican who is a member of the Banking Committee.

Trump has exercised remarkable restraint for months by not simply firing Powell, a restraint encouraged by the ultimate bridle on unbridled executive power, the market, which reacted negatively when Trump first floated the possibility.

Going after Powell with a criminal investigation for possibly lying to Congress in testimony about the Fed building’s renovation reminded me of Justice Ginsburg’s warning, in a concurring opinion in the 1996 Supreme Court case Brogan v. United States, “The prospect remains that an overzealous prosecutor or investigator — aware that a person has committed some suspicious acts, but unable to make a criminal case — will create a crime by surprising the suspect, asking about those acts, and receiving a false denial.” (See the New York Sun editorial, “Martha Stewart and the Law,” May 23, 2008.) It’s an example of the criminalization of policy differences, used against Republicans in Iran-Contra, against Trump in the various criminal investigations against him after his first term over everything from storage of files at Mar-a-Lago to the January 6 riot to his supposed attempts to influence the 2020 election results in Georgia, against Bill Clinton in Whitewater and the Monica Lewinsky investigations.

U.S. Attorney Pirro notes that “The United States Attorney’s Office contacted the Federal Reserve on multiple occasions to discuss cost overruns and the chairman’s congressional testimony, but were ignored, necessitating the use of legal process—which is not a threat.” The best accountability mechanism would be Congress retaking control of monetary policy from the Fed, just like it should retake the tariff policy that it has delegated to the executive branch. In the absence of that, other feedback mechanisms will have to suffice.

Perhaps the most promising way that the Trump-Fed standoff resembles the FDR-Supreme Court standoff is the possibility that the Fed will, “switch in time saves nine” style, do what Trump wants even in the absence of a structural overhaul. On the merits and the empirical data, Trump has been right about inflation and rate cuts, while Powell has been wrong.

Even in the midst of the fight, new data turned up to support Trump’s side of the argument. Since the Liberation Day of tariff announcements on April 2, 2025, part of Powell’s argument has been that he needs to wait and see data about how tariffs will be passed along to consumers in the form of price increases. The 12 month consumer price index data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics this morning shows prices up 2.7 percent on an not-seasonally-adjusted basis, which is a good reading given the dire predictions from economists about how Trump tariffs will fuel inflation.

Non-government data (gold excepted) tells an even more encouraging story on inflation, suggesting the bigger risks to the economy may be on the deflationary side, not the inflationary side.

For example, on energy, the official government data has unleaded regular gasoline down 3.8 percent year over year. But the American Automobile Association, which also tracks gas prices closely, says regular gas is now averaging $2.82 a gallon, down from $3.065 a year ago. That is an eight percent decline, or more than double what the government reports. And the current prices don’t fully account for the possibility of future additional supply coming online eventually owing to developments in Venezuela or Iran. Trump said today at the Detroit Economic Club that gas in some places is below $2 a gallon. “It’s coming down much faster than anyone can even believe,” Trump said.

On rent, the government CPI data reports rent of primary residence up 2.9 percent year over year, a calculation that also influences something called “owners’ equivalent rent of residences,” which is in CPI. Yet YardiMatrix, a commercial data provider that tracks multifamily rents, reports, “The average U.S. advertised rent fell $5 to $1,737 in December, with year-over-year growth dropping 20 basis points to 0.0%.” The Apartment List National Rent Report says, “Rent prices nationally are down 1.3% compared to one year ago. Year-over-year rent growth has been slightly negative for more than two full years, and the national median rent has now fallen from its 2022 peak by a total of 5.9%.”

Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman was saying some of this publicly back in January 2024, telling Barron’s, “Inflation is pretty much at the 2% level already.” As the Barron’s story put it:

While the latest CPI report showed the cost of shelter, mainly tracked by rents and an equivalent measure for homeowners, rose 6.2% year over year, Schwarzman sees a different story. Rather, the increase in rents is currently between zero and 1%, he told Serwer. If true, that would have a meaningful bearing on the overall picture of inflation, since shelter makes up some 30% of how price growth is measured.

“The numbers that the Fed are using are overstated,” Schwarzman said. “[Inflation numbers] are off somewhere around 1.5 to 1.7 [percentage points],” he said.

Truflation, another commercial data provider, says the realtime CPI inflation as of January 12, 2025 was 1.87 percent and realtime PCE inflation was 2.04%. Estimating inflation independently is tricky because there are two distinct steps; figuring out inflation, and figuring out what the government is going to say the inflation number is, using its sometimes less accurate reporting methods. The government number can be what drives some market participants, while others may look to additional sources. As Truflation puts it, “Truflation’s real-time US index is already at 1.74% YoY (down from 1.87%), driven by the Housing sector cooling faster than the BLS surveys can capture…”

And while the Fed sets short-term interest rates nationally, there are also plenty of regional variations. The Wall Street Journal reports that in Phoenix, landlords are so desperate for tenants they are providing incentives: “Amazon gift cards, discounted sports tickets and free moving trucks.” Says the Journal, “Landlords struggling to fill their empty apartments use concessions as a way to draw more tenants without having to cut their baseline prices. Though renters effectively end up paying lower rent, landlords prefer the upfront discount because it is a more temporary hit and allows them to maintain the advertised value of their properties for their lenders and investors.” The term “advertised value” made me wince and chuckle at the same time. Those “lenders and investors” include some of the banks the Federal Reserve is supposed to be among the regulators of. Powell may be gone from the Fed chairmanship by the time those values are more accurately marked, but there may be some bumps along the way there.

Powell has seemed reluctant to give Trump in 2025 and 2026 the rate cuts that he wishes he had given Biden and Harris in 2024. The next Fed chair, like FDR’s Supreme Court, may be less resistant—not in a surrender of Fed independence, but in an acknowledgment of the reality, both empirical and political. The areas ripe for reform go well beyond rates or even a single individual (see “Groupthink Sets in at Powell’s Federal Reserve” and “The Fed Beyond Bessent.”). “Too late” Powell may figure that he’s not going to get any eventual obituary headlines for getting interest rates right, so he might as well hope for some glory as a defender of central bank independence. Open Market Committee meetings in early 2026 are scheduled for January 27-28, March 17-18, and April 28-29. Powell’s term as chair expires in May 2026 (“That jerk will be gone soon,” is the way Trump put it this afternoon at the Detroit Economic Club), but Powell could stick around as a governor through January 2028. It’s not easy to shake a Trump-imposed nickname but it can happen—ask “Liddle Marco,” now the president’s righthand man on national security and foreign policy matters. Maybe it’s not yet too late for Powell to shake the “too late” moniker. And if not him, at least the rest of the Fed may take heed. Remember the switch in time that saved nine.

Trump wants to push the Fed in, in Mr. Stoll's view, in the right direction of lower interest rates...."

How do we know that Mr. Stoll's view is correct? I think presidents want low interest rates because they can accelerate economic growth, which leads to overheating, followed by a recession.

A better system would be to abolish the Federal Reserve and let interest rates be set in the marketplace.

The federal reserve should be more transparent about its reasoning. It should state:

1. To the degree that SCOTUS curbs the tariffs that are not related to national security, the Fed will be more likely to cut rates because, for example, getting aluminum produced with Quebec's comparative advantage due to hydroelectric power lowers input costs.

2. To the degree that oil supply is increased the Fed will be more likely to cut rates because energy costs are a major part of the consumer price index.

3. To the degree that more illegal aliens are removed from the country the Fed will be more likely to cut rates because of an anticipated fall in apartment prices (using the logic of ICE demonstrators, you can't spell PRICE without ICE).

#1 will be a rate-cut consolation to President Trump after a SCOTUS decision curbing tariffs.

#2 and #3 will make clear that the Fed understands that key Trump policies have anti-inflationary effects.