Atlanta Fed GDP Model Now Shows Negative 1.5 Percent Growth

Wide variation in expert forecasts casts doubt on pretense of precision

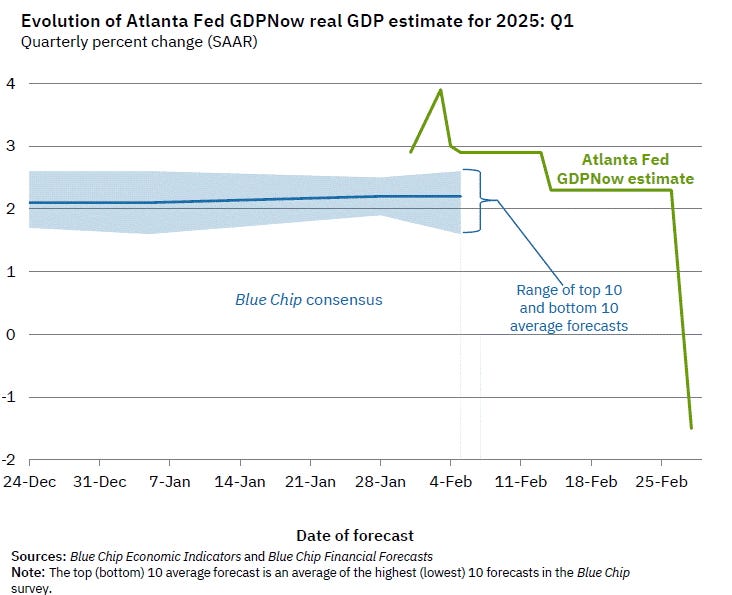

“U.S. Economy on Track for 4 Percent Growth” was the headline here back on February 4 after the Atlanta Fed GDPNow estimate hit 3.9 percent as a measure of the first quarter of 2025.

It was newsworthy at the time because the consensus forecasts—and even ambitious goals—were lower.

Now the Atlanta Fed GDPNow formula has again spit out an outlier estimate—this time on the negative side of things. Today—February 28—the Atlanta Fed model generated a reading of negative 1.5 percent.

Meanwhile, the New York Fed Staff Nowcast, which was also updated on February 28, is at positive 2.94 percent GDP growth, with 4.49 percent or 4.03 percent growth also in the expanded probability path (as well as 1.42 percent or 1.96 percent, for the pessimists out there).

These aren’t reflecting variations in the regional economies—both forecasts are for the national GDP.

What to make of all this?

It’s proof of the press’s, and social media’s, negativity bias. The negative growth reading from the Atlanta Fed is all over the place on X and in the financial media today, while back when it was showing 3.9 percent positive growth, this newsletter was, as far as I can tell, one of the only places sharing the good news. (The Editors is the antidote to negativity bias, we like to say, though we also try to tell it like it is rather than through rose-colored glasses.)

It’s also proof that while the regional Federal Reserve Banks have become much more homogenized and less idiosyncratic and differentiated over recent years, there is still plenty of room for wide variations in forecasts, even among highly sophisticated and extensively trained economic “experts.”

It’s possible (not totally easy, but possible) to make money by taking a side in this difference of opinion. If the growth number has really gone negative, or if, alternatively, it’s outperforming the consensus, then that will ripple through earnings and asset prices.

It’s also illuminating to consider what the implications are for government and public policy. Just as growth affects company earnings and asset prices, it also affects state, local, and federal tax revenue. Faster growth means more tax revenue. Negative growth means more spending on “automatic stabilizers” such as unemployment insurance benefits, food stamps, and health insurance subsidies. In round numbers, the federal government has been spending $7 trillion a year on revenues of $5 trillion a year. Negative 1.5 percent growth would mean less tax revenue, and it could translate into higher spending. There could also be a delayed but modestly positive budget impact if the Fed cuts interest rates to fight unemployment. That would lower the Federal government’s borrowing costs.

Uncertainty about growth rates, or disagreement about reasonable expectations, can make long-term budget planning difficult. With Congress trying to set tax and spending levels for the next decade, the Congressional Budget Office and White House Office of Management and Budget estimates on growth rates dictate how much room Congress has to cut taxes or approve additional spending. The quarter-by-quarter estimates may jump around, but over a decade, the differences between negative 1.5 percent and positive 2.9 percent or positive 3.9 percent compound.

The Editors’ own GDP forecast for Q1 2025 is in the 3 percent to 4 percent positive range, and possibly even higher than that for the whole year and for 2026, but those outlooks are offered with a high level of humility given that even the Fed staff in Atlanta and New York have a wide range of views on the issue. There’s another whole month to go in the quarter. Public policy, in any case, will be better if it’s made with a healthy dose of skepticism about the precision of the expert government forecasts, especially if they are generated by elaborate mathematical models.

Hayek’s Nobel lecture on the pretense of knowledge comes to mind: “Unlike the position that exists in the physical sciences, in economics and other disciplines that deal with essentially complex phenomena, the aspects of the events to be accounted for about which we can get quantitative data are necessarily limited and may not include the important ones.”

Anyway, for the Atlanta Fed, a cynic might say the advantage of having a model that is this jumpy is that whether the Q1 GDP comes in at positive 4 percent or at negative 1.5 percent, either way they can still claim that they called it right.

Recent work: “Following the Money, the Associated Press Moves Left,” is the headline over my latest piece for the Wall Street Journal editorial page. “If Mr. Trump’s rollback of AP’s special access makes readers more skeptical, that may be healthy.” Check it out over at the Journal if you have access and are interested.

I did not include this in the Journal piece, but some readers may be interested to learn also that Quadrivium, the private foundation controlled by James Murdoch, Kathryn Murdoch, and Jesse Angelo, gave the Associated Press $2 million in 2022 to “support AP’s newsroom initiative to establish a centralized climate news desk.” That’s according to Quadrivium’s most recently available tax filings, which are from May 2023.