After UK Vote, Farage Emerges Stronger

Ten “pro-Gaza” candidates also win, including one backing sex-segregation

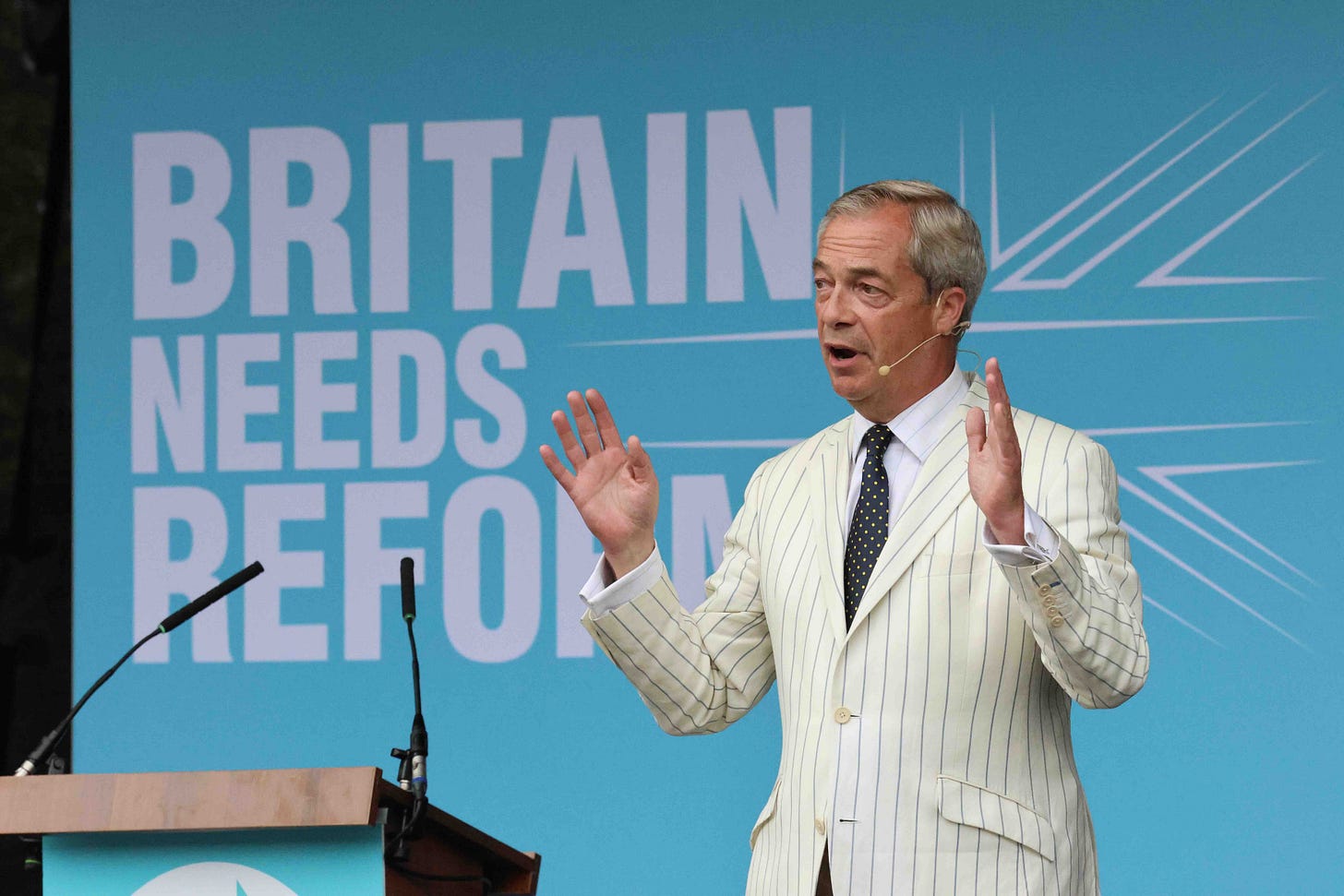

This month’s local government elections in England, alongside a parliamentary by-election (what would be called a special election in the U.S.), did indeed, as previewed here April 28, turn out to be the most significant for perhaps a generation. They were a test for Nigel Farage’s Reform UK to see if it could match its poll numbers in an actual vote — and it proved it could.

Reform won the Runcorn by-election by a margin of just six votes over Keir Starmer’s governing Labour Party. But this constituency 15 miles from Liverpool was in the top 40 safest Labour seats in the country, out of the 411 the Labour party was victorious in at last year’s general election. More startling still was Reform’s success in the local elections. Both Labour and the Conservatives had an unpleasant night while Reform surged ahead.

It is tricky to extrapolate national vote share from local elections that only happen in certain parts of the country, but the number crunchers suggest Reform’s nationwide vote would be around 30 percent based on last Thursday’s performance — 5 per cent above their polling numbers. Labour’s national equivalent vote is estimated at 19 percent and the Conservatives at 18 percent, both well below where they are polling.

So the broad outlines of Britain’s political narrative over the three or four years to the next general election are now clear — the central question will be whether Reform will top the vote then and whether Farage is destined for 10 Downing Street.

Reform will face a number of challenges over the coming years. The party put together 1,600 or so candidates in record time for this year’s local elections. Now 677 of them have been elected. The party, with its limited resources, did its best to vet them, but it is likely at least some eccentrics, nutters, and extremists slipped through. Their opponents and the left-leaning media will do their best to exploit these cases to the max as they are gradually exposed, in an attempt to discredit Reform.

The powers of local government in the UK are also rather limited. Many of Reform’s supporters will now have high expectations, but on issues such as immigration its councillors just won’t be able to do much. Where they can act are on scrapping DEI and other woke initiatives, reversing green anti-car policies and using planning regulations to limit the spread of migrant hostels. Reform will need to show supporters that it has delivered in these areas.

Reform also has an ideological tension at its core. Farage is basically a pro-market, national sovereignty type politician in the mold of Margaret Thatcher, or indeed her great ally Ronald Reagan. But much of its new working-class base is wedded to the UK maintaining a cradle-to-grave welfare state.

This was already seen in this year’s election campaign. Britain’s budget crisis means that Labour, contrary to what it said before last year’s election, has scrapped what was a universal so-called winter fuel payment to retirees of £200 ($265) for those under 80 and £300 ($400) for those above. Labour is also toughening the rules on receiving disability benefits. Reform has made much of opposing these moves, despite Farage’s natural instincts. Reform has also toyed with supporting the nationalization of strategic industries such as steel and water.

As Reform seeks to further appeal to its new base, this tension will only grow and will be difficult for Farage to manage.

Alongside Britain’s briefest prime minister Liz Truss, Farage has been the UK’s most vocal Donald Trump supporter. Unlike in the Canadian and Australian elections of last week — in both countries the major party of the Right was badly damaged by supposed closeness to the American president — this had no discernible effect on England’s vote. Indeed Trump hardly featured in public debate about the elections; immigration and the perceived failures of the old parties played much the biggest role.

But if Farage makes it to Downing Street, might we see him working in close tandem with Trump? This will certainly be the instinct of Reform’s leader, but timing will likely ensure this does not materialize.

Apart from a brief interlude between 2011 and 2022, UK general elections are not held at a fixed time. A parliament expires on the fifth anniversary of its first meeting after the previous vote, but elections are invariably called before that by the governing prime minister. In practice a governing party calls an election at the earliest point after four years when it is confident of winning an election.

This means that the earliest likely date of the next general election would be the summer of 2028. If Reform were to win this, Trump and Farage would overlap for about six months. But Starmer has an impregnable parliamentary majority, and if it looks like Reform might win he is most unlikely to go to the country then. It is much more likely if there is a likelihood of a Labour defeat that Starmer won’t ask for an election until the spring of 2029— in other words, after Trump has left office.

There is one more takeaway from the local elections that is worth noting. The votes largely did not take place in heavily Muslim parts of the UK. But in those areas where the vote happened and there is a substantial Muslim population, Islamist “pro-Gaza” candidates standing as independents did do well. Around ten such council candidates were elected, including Maheen Kamran — an 18-year old woman whose platform includes the sex-based segregation of public spaces. Their success does not augur well for when London elects its councils next year. Sectarian politics is now a feature of UK elections.

If Reform and Conservatives split the vote on the Right, Labour will benefit, winning many ridings even if the Left gets fewer votes. This is a classic situation that can be fixed by Approval Voting, in which voters specify their one or more approved candidates.