What Caused the 1970s Inflation? And What Finally Cured It?

It wasn’t all about “political pressure on the Fed”

A theory has taken hold among reporters for major news organizations about the causes of inflation in the 1970s. It’s of more than merely historical interest, because the context from the past is being wielded as a weapon against further rate cuts by the Fed.

The Wall Street Journal’s reporter covering the Federal Reserve, Nick Timiraos, put it this way in a news article in today’s paper: “Central bank independence, or the freedom to take unpopular steps in the economy’s long-run interest, emerged from the lessons of the 1970s, when political pressure on the Fed contributed to runaway inflation,” Timiraos wrote.

The New York Times reporter covering the Fed, Colby Smith, has been sounding similar notes. Here’s how Smith put it in a New York Times article in July 2025:

Arthur Burns, who led the central bank from 1970 to 1978, serves as a cautionary tale for the perils of a politicized Fed. He is remembered as an ineffective chair, having bowed to political pressure by President Richard M. Nixon and unleashing one of the worst bouts of inflation in the country’s history.

Mr. Nixon, who had previously appointed Mr. Burns as an adviser, sought easier monetary policy in order to juice the economy ahead of the 1972 presidential election. What resulted was a “stop-go” approach to interest rate adjustments, with the Fed flip-flopping between raising borrowing costs and lowering them even before price pressures had been fully stamped out.

Combined with a series of geopolitical shocks that caused oil prices to spike in the late-1970s, inflation took off.

Smith at least mentions oil prices, and Timiraos hedges with “contributed to” rather than the more direct “caused.” Even so, the whole situation is a good example of how groupthink—reporters on the same beat all writing the same thing—and source capture—reporters relying on the sources at the institution they cover rather looking for more independent and original ideas—dis-serves readers and obscures the truth.

Sure, there is evidence from the Nixon White House tapes that President Nixon spoke to Fed Chairman Arthur Burns. An article by Burton A. Abrams in the Fall 2006 issue of Journal of Economic Perspectives, “How Richard Nixon Pressured Arthur Burns: Evidence from the Nixon Tapes,” gives the evidence. But the taped interactions are pretty mild—mainly Nixon musing about how he does not want to lose the 1972 election, Burns reporting back on rate cuts, and Nixon responding with praise. The most noteworthy thing in the article comes from Nixon aide John Ehrlichman’s 1982 book, Witness to Power, in which Ehrlichman describes an October 23, 1969 meeting between Nixon and Burns, who had just been nominated as Fed chair:

“My relations with the Fed,” Nixon said, “will be different than they were with [previous Federal Reserve chairman] Bill Martin there. He was always six months too late doing anything. I’m counting on you, Arthur, to keep us out of a recession.”

“Yes, Mr. President,” Burns said, lighting his pipe. “I don’t like to be late.”

Given President Trump’s nickname for Fed Chairman Jerome Powell—“too late”—it’s something to see the “too late” description used by Nixon for Bill Martin. It suggests that delayed reaction is a recurring pitfall of central banking. A lot of other things—communications, computing power—have gotten a lot faster between 1969 and 2025, but excessive slowness is still a hazard for central bankers, at least in the eyes of presidents.

The storyline that Nixon pushing the central bank to lower rates so that he could win the 1972 election is what unleashed the 1970s inflation has some problems, though. A useful primary source is Nixon’s August 15, 1971 “Address to the Nation Outlining a New Economic Policy.”

Here’s how Nixon put it in that speech: “in the 4 war years between 1965 and 1969, your wage increases were completely eaten up by price increases. Your paychecks were higher, but you were no better off. We have made progress against the rise in the cost of living. From the high point of 6 percent a year in 1969, the rise in consumer prices has been cut to 4 percent in the first half of 1971. But just as is the case in our fight against unemployment, we can and we must do better than that.”

In other words, inflation was 6 percent in 1969, before Arthur Burns took over as Fed Chair on February 1, 1970. The supposedly overly political Burns had brought it down to 4 percent. It’s almost as if the inflation were driven not by Nixonian pressure on the Federal Reserve but by Lyndon Johnson’s election-year spending binge, which brought federal outlays in 1968 to 19.8 percent of GDP—the highest since 1953—and caused a federal budget deficit of 2.8 percent of GDP, the largest since 1946, according to the historical tables maintained by the White House Office of Management and Budget.

The Reagan years showed that pro-growth policies can manage deficits, especially if the deficits come from tax cuts and defense spending rather than government waste. But the Nixon policies were the opposite of pro-growth. In the same August 15, 1971 speech, Nixon ordered “a freeze on all prices and wages throughout the United States for a period of 90 days.” He also directed the treasury secretary, John Connally, “to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold or other reserve assets.” Nixon claimed that, “The effect of this action, in other words, will be to stabilize the dollar,” but that might have been the biggest lie that Nixon ever told.

As a State Department history later recounted, the effect was to end the dollar’s congressionally set price of one thirty-fifth of an ounce of gold. Here’s how the State Department put it:

After months of negotiations, the Group of Ten (G–10) industrialized democracies agreed to a new set of fixed exchange rates centered on a devalued dollar in the December 1971 Smithsonian Agreement. Although characterized by Nixon as “the most significant monetary agreement in the history of the world,” the exchange rates established in the Smithsonian Agreement did not last long. Fifteen months later, in February 1973, speculative market pressure led to a further devaluation of the dollar and another set of exchange parities. Several weeks later, the dollar was yet again subjected to heavy pressure in financial markets; however, this time there would be no attempt to shore up Bretton Woods. In March 1973, the G–10 approved an arrangement wherein six members of the European Community tied their currencies together and jointly floated against the U.S. dollar, a decision that effectively signaled the abandonment of the Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system in favor of the current system of floating exchange rates.

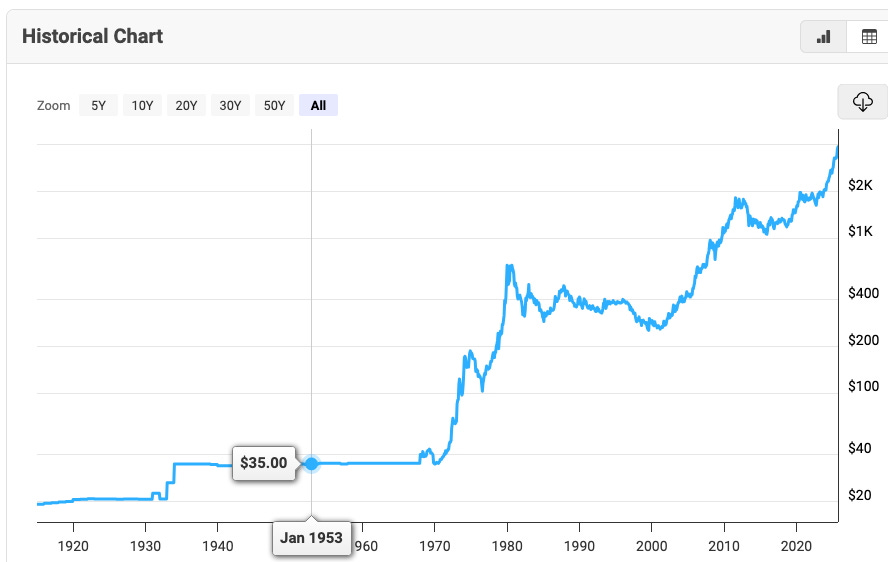

The December 1971 dollar was set at $38 per ounce of gold; by 1973 it was ostensibly $42 per ounce of gold, but the market wasn’t going along. The chart tells the story:

These were decisions made by presidents and treasury secretaries and to some degree Congress. Interest rates set by the Federal Reserve were much less of a factor. It took a pro-growth administration to finally defeat inflation, but the main hero wasn’t so much Fed Chairman Paul Volcker but the other players. Here is the history of it:

The Reagan tax cut had antecedents in the Harding, Coolidge, and Kennedy administrations, but its birthdate was in May 1974, at a conference on “The Phenomenon of Worldwide Inflation.” The meeting was sponsored by the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research and the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace. The list of participants included the Hoover Institution’s Martin Anderson, who would advise Reagan’s 1976 and 1980 presidential campaigns and then serve in the Reagan administration as domestic policy adviser and a member of the economic policy advisory board. Among the crowd were three economists who would eventually win Nobel prizes: Robert Lucas, Robert Mundell, and Edmund Phelps. Jacob A. Frenkel was there—he would serve nearly a decade as the governor of the Bank of Israel, Israel’s top central banker. Norman B. Ture, who had worked on the Kennedy tax cut as an aide to House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Wilbur Mills, and who would join the Reagan administration as undersecretary of Treasury for tax and economic affairs, was in attendance. So was Arthur Laffer, then teaching at the University of Chicago.

The really consequential interaction at the May 1974 inflation conference that took place at the American Enterprise Institute’s Washington headquarters, though, was the first meeting between Mundell and Jude Wanniski, who was on the staff of the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal. The two clicked immediately; by one account, “when they returned to New York after the conference, Wanniski slept on Mundell’s couch for several days instead of going home to New Jersey.” Wanniski grasped the explosive newsworthiness of Mundell’s idea that the inflation and slow growth plaguing the 1970s economy could be defeated by a combination of tight monetary policy and tax cuts. Wanniski went on to share this idea energetically with readers. Under the headline, “It’s Time To Cut Taxes,” the December 11, 1974, Wall Street Journal carried Wanniski’s bylined interview with Mundell. Wanniski conceded that Mundell’s prescription “is obviously not part of mainstream thinking in the United States.” He quoted Mundell, who taught at Columbia University: “The level of U.S. taxes has become a drag on economic growth in the United States…The national economy is being choked by taxes — asphyxiated.” Wanniski explained, paraphrasing Mundell and Laffer, that tax cuts affect incentives. “With lower taxes, it is more attractive to invest and more attractive to work; demand is increased but so is supply.”

Wanniski returned to the subject in the Spring 1975 issue of The Public Interest, a journal edited by Irving Kristol. In an article headlined “The Mundell-Laffer Hypothesis—a new view of the world economy,” Wanniski summed it up: “If the world economy has inflation and unemployment at the same time, the proper policy mix is tight money and fiscal ease. The latter should preferably take the form of tax reductions…” A footnote explained what became known as the Laffer Curve. It quoted Laffer: “There are always two tax rates that produce the same dollar revenues. For example, when taxes are zero, revenues are zero. When taxes are 100 per cent, there is no production, and revenues are also zero. In between those extremes there is one tax rate that maximizes government revenues.” Wanniski wrote that under the right circumstances, a tax cut “raises output and the tax base, besides making the economy more efficient.” The columnist Robert Novak later wrote that the article “really launched the supply-side movement by introducing to general readers the teaching of Laffer and Robert Mundell.”

Kristol got a $40,000 grant for Wanniski to do a stint at the American Enterprise Institute, where Kristol was a fellow, and to expand the Public Interest article into a book on supply-side economics. The Way the World Works, edited by Midge Decter for Basic Books, hit bookstores in 1978, featuring a blurb by Kristol on the cover.

Meanwhile, Laffer, in December 1975, had lunch in Los Angeles, at Martin Anderson’s invitation, with Reagan, by then the former governor. In the summer of 1976, Laffer moved to Palos Verdes Estates, took up a job teaching at the University of Southern California, and, through a connection to drugstore magnate Justin Dart, began seeing Reagan fairly frequently at social events. In September of 1976, a Reagan newspaper column was headlined “Tax Cuts and Increased Revenue.” It pointed out that after both President Warren Harding and President John Kennedy cut federal income tax rates, “federal revenues went up instead of down.” Wrote Reagan, “Since the idea worked under both Democratic and Republican administrations before, who’s to say it wouldn’t work again?” Reagan, who as a movie star had paid a 94 percent top income tax rate, did not need a lot of convincing that the rates could use some lowering; even a 1966 profile of him in Esquire reported, “his reading runs to tomes on tax reform.” In January 1974, he sent William F. Buckley Jr. a note of thanks for the gift of Buckley’s book, Four Reforms, which proposed eliminating the progressive income tax system and its morass of deductions and exemptions and replacing it instead with a 15 percent flat tax.

The idea of tax cuts was gradually gaining new momentum. As a lame duck Treasury secretary in President Ford’s administration, William Simon issued a January 17, 1977, report, “Blueprints for Basic Tax Reform.” The report proposed tax simplification combined with rate reductions that would lower the top federal income tax rate to either 38 percent or 40 percent from 70 percent. Simon’s 1978 book A Time for Truth, with a preface by Milton Friedman, denounced “the tax burden growing steadily to finance the redistribution process.” It urged, “the principle of ‘no taxation without representation’ must again become a rallying cry of Americans.” It sold 2.5 million copies. Also in 1978, President Carter signed into law the Steiger Amendment, which cut the capital gains tax to 28 percent from the effective 49.875 percent maximum level to which it had been raised by Nixon and Ford.

In August of 1979, Anderson wrote “Policy Memorandum No. 1” for Reagan’s presidential campaign. It began, “By a wide margin the most important issue in the minds of voters today is inflation.” Anderson’s recommended cure? “Reduce the rate of growth of federal expenditures” and “simultaneously stimulate the economy so as to increase revenues in such a way that the private share grows proportionally more than the government share.” As the memo put it, “speed up economic growth…reduce federal tax rates.” In August of 1979, though, some of the key tax-cut advocates—Wanniski, Laffer, Kristol, Paul Craig Roberts—were nursing hopes of a presidential campaign by Jack Kemp, a congressman from Buffalo, New York, who had been a professional football quarterback for the Buffalo Bills. Kemp’s endorsement of Reagan, and Reagan’s reciprocal formal endorsement of tax cuts, united the so-called supply-siders in the Reagan camp. During Reagan’s 1980 general election campaign, key economic advisers included Milton Friedman, Arthur F. Burns, Alan Greenspan, and William Simon.

In his July 1980 speech accepting the Republican presidential nomination, Reagan spoke of “a great national crusade to make America great again.” He linked tax cuts to growth: “When I talk of tax cuts, I am reminded that every major tax cut in this century has strengthened the economy, generated renewed productivity and ended up yielding new revenues for the government by creating new investment, new jobs and more commerce among our people.”

By July 1981, when President Reagan took to national television to urge the American people to press Congress for permanent tax cuts (“they need to hear from you”), he was confident. “The best way to have a strong foreign policy abroad is to have a strong economy at home,” Reagan said. “If the tax cut goes to you, the American people… that money returned to you won’t be available to the Congress to spend, and that, in my view, is what this whole controversy comes down to. Are you entitled to the fruits of your own labor or does government have some presumptive right to spend and spend and spend?” He concluded his plea: “It’s been the power of millions of people like you who have determined that we will make America great again.”

Oh, and by the way, when inflation finally was defeated in the 1980s, it wasn’t only an environment of tax cutting. It was also a moment of lots of political pressure on the Fed to cut rates, from President Reagan’s Treasury Secretary, Donald Regan, from Jack Kemp, from Jim Wright, from Senator Robert Byrd, as I wrote about in May (“Trump Calls for Fed to Cut as New Paper Highlights Role of Regional Reserve Banks.”)

Sure, an overly political Fed that keeps interest rates too low for too long is an economic risk. But in terms of summing up the causes of the 1970s inflation, that’s a gross oversimplification that misses the more important points. And in terms of what finally ended the 1970s inflation, there were factors other than Paul Volcker, too.

Timiraos, who graduated from Georgetown in 2006, and Smith, a 2013 Brown graduate, may be too young to remember or understand any of this, but the markets seem to, which may be why stock prices are telling more of a 1980s story than a 1970s story, and why gold prices, while sounding some caution, also are not a 1970s replay.

Maybe it will all change if and when Trump gets full control of the Federal Reserve. But maybe not. Trump, after all, get elected in part because of Bidenflation. His success rests on defeating inflation, not on recreating it with overly loose monetary policy or a repeat of Nixon’s mishandling of the dollar. Trump may borrow the “too late” insult from Nixon. But for economic success he and his team need to be more like Reagan.

Thank you: If you know someone who would enjoy or benefit from reading The Editors, please help us grow, and help your friends, family members, and associates understand the world around them, by forwarding this email along with a suggestion that they subscribe. Or send a gift subscription. If it doesn’t work on mobile, try desktop. Or vice versa. Or ask a tech-savvy youngster to help. Thank you to those of who who have done this recently (we see the results, and they are encouraging) and thanks in advance to the rest of you.

A superbly succinct piece with a lesson that is as relevant now as it was then. Should be compulsory reading for everyone who thinks they know what the Fed should do, which is pretty much everyone on both sides of the Maga divide.

The great ideas of domestic policy in the 1980 election were Milton Friedman's book and TV series "Free to Choose" and Jude Wanniski's book "The Way the World Works" (my favorite is the chapter "The Electorate Understands Economics".

The great ideas of the 1994 congressional elections were in Newt Gingrich's Contract with America.

Other elections in the past 5 decades were shallow in comparison.