Trump’s Pronoun Problem

“Their war” in Gaza? Not exactly.

“It’s not our war. It’s their war,” President Trump said on his first day back in office, responding to a question about whether the Gaza ceasefire will hold.

The most hopeful way to parse those pronouns is that Trump intends a clean break from the Biden administration’s failed efforts to micromanage Israel’s war tactics. Biden’s public advice—to limit strikes against Iran, not to escalate against Hezbollah in Lebanon, not to go into Rafah in southern Gaza—wound up as the worst of all worlds. Washington looked foolish when Israel scored victories by disregarding Biden’s advice, and Israel’s enemies blamed America anyway for whatever Israel did. A little separation might be a useful corrective.

There’s also a danger, though, that Trump’s pronouns will wind up giving the American public and the world a false impression. The Gaza war, after all, is just one battle in a long war that, whether Trump likes it or not, is inescapably ours.

By “ours,” I mean America’s and civilization’s war against the barbaric terrorists who want to conquer Israel, Europe, and America, subjugating the Jewish state, Christendom, and modernity to radical Islamist rule.

This is not an issue confined to Israel. The October 7, 2023, terrorist attack that triggered the Gaza-Israel war killed 48 Americans. They are only the latest in a long series of American casualties from terrorism directed and inspired by Iran, ISIS, and al Qaeda.

Trump sometimes conveys the mistaken concept that this war has somehow been America’s choice. On Tuesday, he said of his own former national security adviser, John Bolton, “He was a warmonger. He’s the one that got us involved, along with Cheney and a couple others, convinced Bush, which was a terrible decision, to blow up the Middle East.” Trump added, “We got nothing out of it, except a lot of death. We killed a lot of people.”

Yet it wasn’t John Bolton or Vice President Cheney who “got us involved” in the Middle East. It was the decision by Al Qaeda terrorists to hijack airplanes and fly them into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon on September 11, 2001. They had been emboldened by a series of deadly attacks on American targets that were met without decisive responses—the 1996 attack on U.S. air force personnel at Khobar Towers in Saudi Arabia, the 1998 bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania, the attack on the USS Cole in 2000.

Prime Minister Netanyahu has tried to explain this. “Iran's regime has been fighting America from the moment it came to power,” Netanyahu said in his July 2024 address to Congress, mentioning the 1979 takeover of the American embassy in Tehran.

Netanyahu went on, “My friends, if you'd remember one thing — one thing from this speech, remember this: Our enemies are your enemies, our fight is your fight, and our victory will be your victory.”

If Netanyahu’s position is “our fight is your fight,” and Trump’s position is “It’s not our war. It’s their war,” the second Trump administration may be off to a discordant relationship with its key Middle East ally.

Whose war it is depends not only on Trump or Netanyahu but also on Iran. The U.S. government has said that Iran tried to interfere in the 2020 and 2024 U.S. elections, hack into Trump’s campaign communications, and plotted to kill Trump. Maybe Trump doesn’t consider any of those things acts of war.

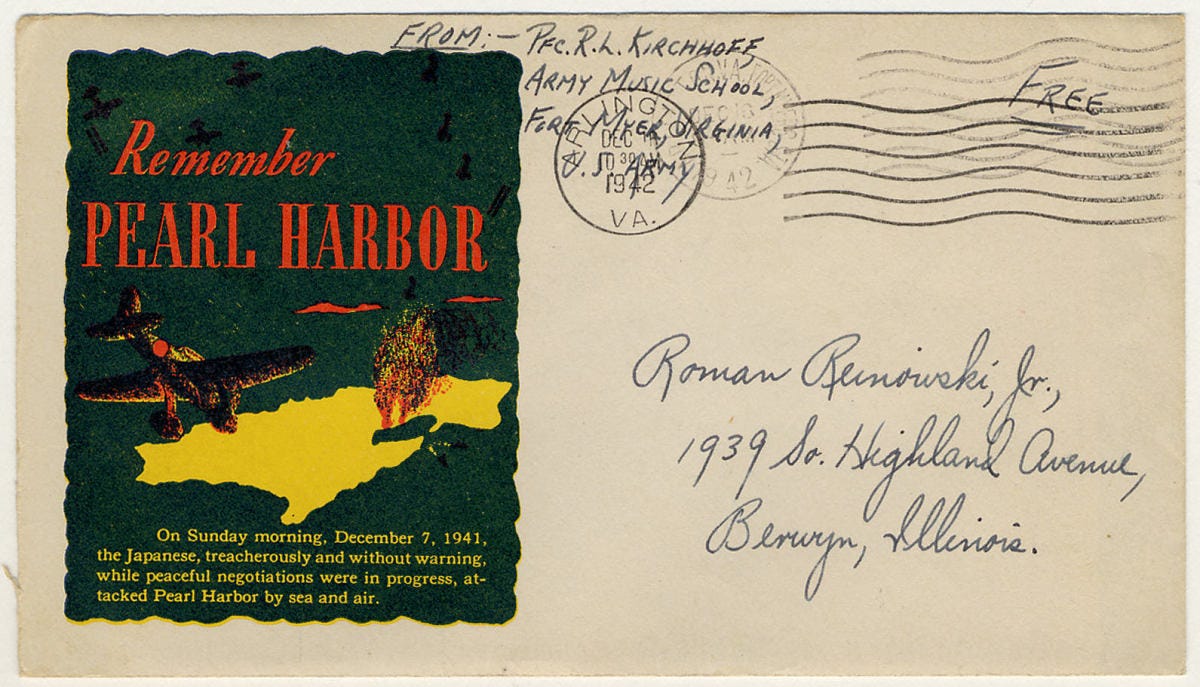

The risk is that there are Iranians with an apocalyptic point of view hoping to provoke a confrontation. One precedent in American history for realizing only belatedly that a war we thought was “theirs” was indeed “ours” is Pearl Harbor.

Let us hope it does not require America suffering the shocking pain of a surprise attack for the president eventually to get the pronouns correct.

It is good analysis to sketch out the various possible meanings and then follow events to see which fits best with emerging data.