Trump Is Right About the Associated Press

Plus, what’s happening at the Kennedy Center

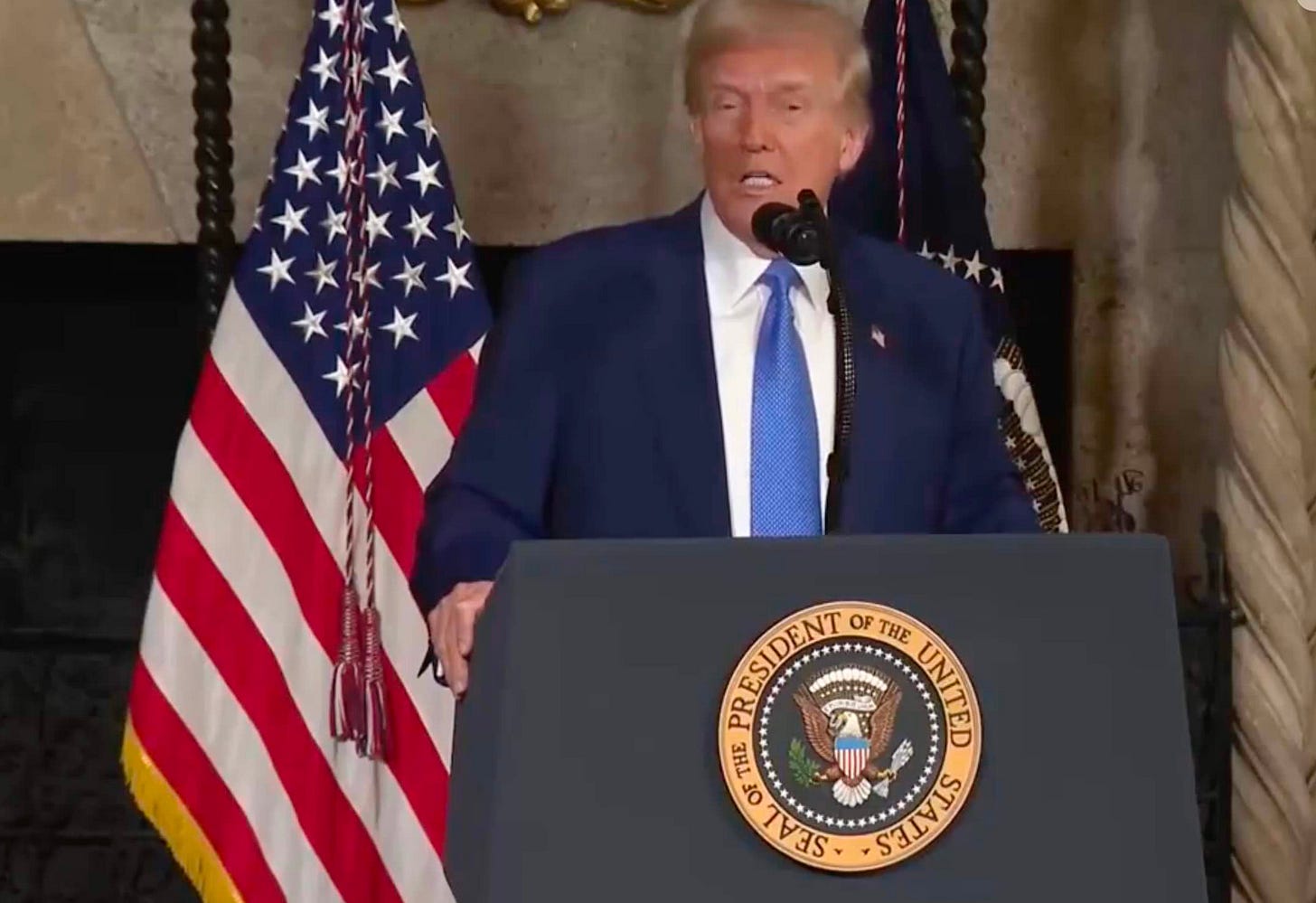

President Trump was asked yesterday about his administration restricting some access to the Associated Press wire service because of its refusal to rename the Gulf of Mexico as the Gulf of America. “We’re gonna keep ’em out until such time as they agree that it is the Gulf of America,” Trump said. “The Associated Press, as you know, has been very, very wrong on the election, on Trump and the treatment of Trump, and other things having to do with Trump and Republicans and Conservatives. They are doing us no favors, and I guess I am doing them no favors. That’s the way life works.”

The chief White House correspondent of the New York Times, Peter Baker, who is also an analyst for MSNBC, posted to social media in support of the Associated Press: “We stand with the @AP which is resisting government pressure attempting to dictate how it writes about the news. This is exactly what the founders had in mind when they crafted the First Amendment.”

President Obama once attempted in a somewhat similar way to cut back on access to Fox News, with then Obama aide David Axelrod insisting that Fox News wasn’t a real news organization.

I earned money during college by working part-time as the Associated Press’s Harvard stringer, a job that consisted mainly of getting up early in the morning and telephoning the AP Boston bureau, reading the news editor the headlines from the Crimson, and then faxing over any stories that the editor was interested in for the AP wire. It was a good job to have in college, and since then I’ve always admired the AP for its straight-down-the-middle, just-the-facts approach and reputation. (And I also use the anecdote as a way to explain how the internet has allowed for increased productivity in the news business, as nowadays the AP Boston bureau can just read the Crimson headlines on the internet without having to pay a Harvard undergraduate to telephone and fax.)

Unfortunately, there’s new and additional evidence that AP has indeed gone off the rails—and it goes well beyond whether the organization prefers the term Gulf of Mexico or Gulf of America.

The piece that proved it for me was this long AP article attacking Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Cisco, Dell, Oracle, IBM, and Palantir for having Israel as a customer. The AP describes them as “among a legion of U.S. tech firms that have supported Israel’s wars in recent years.” Instead of calling the people Israel is killing terrorists, the AP describes them as “alleged militants.” It’s a terrible story that looks like it could have been written, bought and paid for by proponents of boycotting Israel. And then at the very end of the article comes a disclosure: “The Associated Press receives financial assistance from the Omidyar Network to support coverage of artificial intelligence and its impact on society.” Omidyar is notoriously anti-Israel; another press outlet it funds, the Intercept, has been busy attacking the New York Times for being insufficiently pro-Hamas.

Anyway, any outlet that takes money from Omidyar to publish an article that conveys an underlying assumption that American tech companies should refuse to sell products and services to the Israeli military has functionally destroyed whatever reputation it once had as an impartial and journalistically independent outlet. It’s sad to see, because that sort of credibility is both valuable and rare, and once it is destroyed, it’s difficult to recover.

The First Amendment says Congress shall make no law abridging the freedom of the press. Trump’s tactics and Obama’s are debatable, and some district judge may yet declare them illegal. To my mind, though, there’s a difference between sending police in to raid a newsroom and padlock the doors—a clear First Amendment violation so long at the newsroom isn’t totally a ruse for some foreign intelligence operation or genuinely criminal enterprise—and not inviting a news outlet into the Oval Office or along on Air Force One, which is more of a gray area. The AP probably qualifies as “press” under the First Amendment notwithstanding its egregious partisan tilt. For Trump to point that tilt out to the public isn’t a First Amendment violation, it’s a public service. To the extent that Trump’s comments create more skeptical news consumers, it’s more useful than a lot of expensive government programs designed to combat misinformation or disinformation.

Plenty of pro-Trump outlets—say, American Greatness, operated by Donald Trump Jr.’s business partner Chris Buskirk—deserve similar skepticism and scrutiny. But the notion that the Omidyar-funded AP is somehow neutral or nonpartisan and beyond scrutiny or criticism is just bizarre. It may be a touchy issue for Baker in part because left-leaning charities are also funding reporters and editors at the New York Times, as if the Ochs-Sulzberger family is in need of charitable dollars.

Abe Greenwald’s “final thought” from his February 17 Commentary daily newsletter may apply also here: “A final thought. Some days, I write positively about the Trump administration. Some days, negatively. As a result, I get criticized as either a MAGA true believer or a hopeless victim of Trump Derangement Syndrome.” It speaks well of Commentary these days that its audience, like the one here, is a big enough tent that it includes readers making both complaints. Anyway, my main intent here is less to pass judgment on Trump—readers can judge for themselves—but to call attention to and provide context for the changes at the Associated Press.

What’s happening at the Kennedy Center?: Toward the end of an account about Trump-imposed changes at Washington’s John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, the New York Times includes this passage:

In a bit of symmetry, both Mr. Trump and Mr. Biden removed their predecessor’s press secretaries from boards before their terms were up. Mr. Trump removed Karine Jean-Pierre, who had been Mr. Biden’s press secretary, from the Kennedy Center board. Mr. Biden removed Sean Spicer, Mr. Trump’s former press secretary, from the Naval Academy’s board of visitors.

Mr. Spicer was removed from the Naval Academy board along with Russell Vought, who had been the director of the Office of Management and Budget during Mr. Trump’s first term and was recently reappointed to the post in his second term. The two men sued the Biden administration, arguing that Mr. Biden did not have the power to remove them. A district court in Washington sided with the Biden administration, saying board members had no such protections.

In 2023, a federal appeals court in Washington came to a similar conclusion in a case involving another Trump official, Roger Severino, who was removed by Mr. Biden from a position on the council of the Administrative Conference of the United States.

This is illuminating because it shows the hypocrisy on both sides. The Trump side, which is now using executive power to exert control of these boards and institutions, had claimed it was illegal when Biden did it to them. And the Biden side, which is upset now about Trump using executive power to exert control of these boards and institutions, had no such compunctions back when Biden was the one exerting the control. It’s almost enough to make one suspect that both their views are not rooted in principled or consistent theories about executive power and its limits under the Constitution. It suggests, instead, that these are outcome-based approaches that are situational and dependent on whether one’s own team or the opposing team controls the presidency.

Recent work: “What the New York Times Left Out of Its Jerusalem Bookstore story,” is the headline over my latest article for the Algemeiner. There is no paywall there, so anyone interested in that can read the article there by clicking on the hyperlinked headline.

It is not necessarily hypocritical to use a tactic that you thought was illegal when used against you, but was then ruled legal by the courts. If it is declared legal, you are not obligated to leave the tactic for exclusive use by your opponents.

Such situations become more questionable when your objection is that a action is wrong, though legal. A classic example was when Harvard philosopher Robert Nozick, an opponent of rent control, took legal action against his landlord for violating the rent control law. Nozick thought he was not obligated to leave the monetary benefit for a renter under rent control for exclusive use by rent control proponents.