Trump Gives His Universal Recipe for Electoral Success

Plus, research finds rising despair among younger U.S. workers

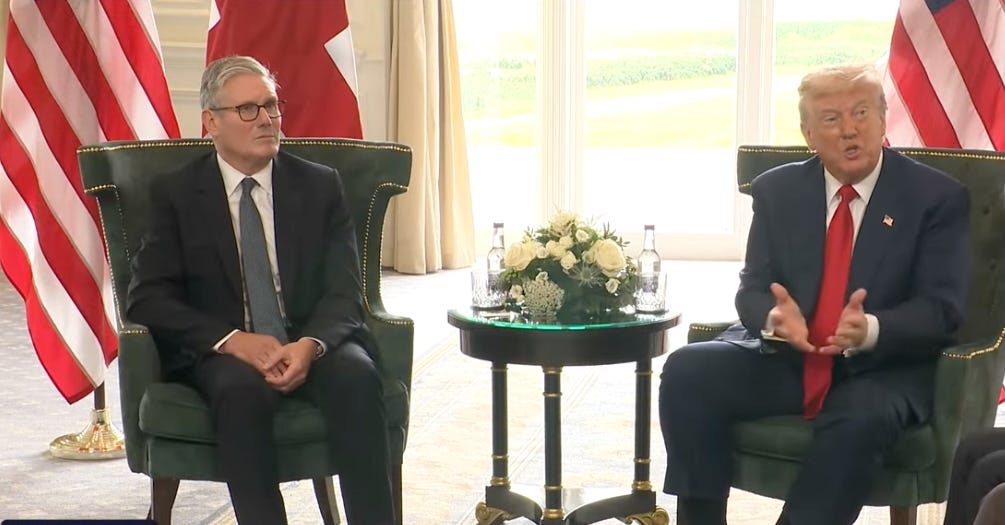

President Trump appeared today with the prime minister of Britain, Keir Starmer. The two of them answered questions from reporters for more than an hour after their meeting, discussing a wide range of topics—trade and tariffs, humanitarian aid to Gaza, the Israeli hostages, Russia’s war with Ukraine, Jeffrey Epstein. The most striking moment to me was when Trump took a step back from the policy details of the day and offered a more general-purpose prescription for political success.

“You know, politics is pretty simple,” Trump said. “Generally speaking, the one who cuts taxes the most, the one who gives you the lowest energy prices and the best kind of energy, the one that keeps you out of wars…You know, you have a few basics, and you can go back a thousand years, a million years, whoever does these things — low taxes, keep us safe, keep us out of wars, no crime, stop the crime.”

Trump said he won in 2024 “because I was very strong on immigration. … so I think it's a huge factor in any election, not just this election, but in any election. I think the one that’s toughest and most competent on immigration is going to win the election. But then you add low taxes, and you add the economy.” (In a little-noticed comment at a July 8 cabinet meeting, Trump said about immigration, “I don’t want to be too tough on it. We want to be humane…sometimes you can be too strong.”)

In another appearance with Starmer today, before their meeting, Trump said, “I have a theory that low taxes bring growth…I find that when you lower taxes, you get growth.”

In the U.S. context, “keep us out of wars” isn’t always a requirement for electoral victory. Lincoln was re-elected in 1864 amid the Civil War, Franklin Roosevelt was re-elected in 1944 during World War II, George W. Bush was re-elected in 2004 with a war ongoing in Iraq, and President Madison was reelected during the War of 1812.

Trump’s aversion to wars is well known at this point. There’s a danger that our enemies hear Trump talking about keeping out of wars and conclude that they can get away with doing anything they want—seize Taiwan, invade Finland, launch cyberattacks against American targets—without risking American military retaliation. Trump went a distance toward allaying such concerns with the U.S. airstrikes against Iranian nuclear facilities and again with the July 25, 2025 deadly U.S. attack in al-Bab, Syria, on an ISIS leader, Dhiya’ Zawba Muslih al-Hardani, and his his two adult ISIS-affiliated sons, Abdallah Dhiya al-Hardani and Abd al-Rahman Dhiya Zawba al-Hardani.

On the tax point, some Democrats have tried to maneuver politically to be on both sides of the issue by supporting lower taxes for middle-class or working taxpayers while also supporting higher taxes on “the rich” for budget-balancing or financing-spending reasons or just plain for punishing successful people and redistributing their wealth for “equity” reasons. The strongest Republican candidates are able to point out the problems with that approach, but Democrats with weaker opponents are sometimes able to get away with it.

Monday Is NBER Day: Monday is the day that the National Bureau of Economic Research releases new working papers. Two out today caught my eye.

In “The Risk, Reward, and Asset Allocation of Nonprofit Endowment Funds,” Andrew W. Lo and Egor V. Matveyev of the MIT Sloan School of Management and Stefan Zeume of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign look at a large set of nonprofit organization tax returns and make some general findings about endowment funds.

Over fiscal years 2008 to 2020, the endowment funds achieved “average net investment return” of 4.3%, over a period in which the S&P 500 returned 8.0% annually and a “conservative multi-asset benchmark appropriate for endowments earned an average annual return of 6.7% over the same period.” The problems may be overly conservative asset allocations or overly high fees paid to internal or external money managers who aren’t adding value to justify the fee.

Large private university endowments get a lot of attention but there are lots of smaller instititions—hospitals, museums, environmental groups—that also have endowments.

In “Rising Young Worker Despair in the United States,” David G. Blanchflower of Dartmouth and Alex Bryson of University College London look at the changing age pattern of happiness. It used to be a U shape, where young people were happy, middle-age people were unhappy, and older people were happier. Or, if what you are measuring is unhappiness rather than happiness, the chart looks like a hump that peaks in middle age (at about age 54). More recently, that profile has changed. The paper speaks of a “shift in the age-pattern of mental despair from a hump-shape to a monotonic decline in age.” And the researchers tie that change to unhappy younger workers. “We find the hump-shape in age still exists for those who are unable to work and the unemployed. The relation between mental despair and age is broadly flat, and has remained so, for homemakers, students and the retired. The change in the age-despair profile over time is due to increasing despair among young workers.”

Blanchflower and Bryson conclude: “In this paper we have confirmed that the mental health of the young in the United States has worsened rapidly over the last decade, as reported in multiple datasets. The deterioration in mental health is particularly acute among young women….Increasing access to the internet and smartphones seem to be the culprits.” (Bold added for emphasis by the editor in this paragraph and the previous one.)

Blanchflower and Bryson don’t make a connection with Zohran Mamdani’s youth-driven New York City mayoral campaign, or with Gallup polling showing declining pride in America among young adults. But if you have the context that younger workers, especially women, are afflicted with despair and “deterioration in mental health,” then maybe the lack of patriotism and the interest in the Israel-hating socialist mayoral candidate become slightly easier to understand. Blanchflower and Bryson are economists, not mental-health clinicians such as psychologists or psychiatrists or political scientists. The findings deserve to be treated as skeptically as any other academic or social science research. But they are worth keeping an eye on. With luck this cohort will get happier and more patriotic as it ages.

Thank you: Paying subscribers are what stave off worker despair here at The Editors. This is a reader-supported publication. If you appreciate the information and analysis and the news that you do not find elsewhere, please ensure your full access to all the content and help to sustain our editorial independence by becoming a paid subscriber today. The cost is as little as $1.54 a week. Many thanks to those of you who already have joined.

Know someone who would enjoy or benefit from reading The Editors? Please help us grow by forwarding this email along with a suggestion that they subscribe. Or send a gift subscription: