The Economist Who Made the MAGA Case on Tariffs—in 1945

Plus, new anti-Israel vandalism attacks at Harvard site

“Among the economic determinants of power, foreign trade plays an important part….Foreign trade has two main effects upon the power position of a country. The first effect is certain to be positive: By providing a more plentiful supply of goods or by replacing goods wanted less by goods wanted more (from the power standpoint), foreign trade enhances the potential military force of a country. This we may call the supply effect of foreign trade. It not only serves to strengthen the war machine of a country, but it uses the threat of war as a weapon of diplomacy…The attempt to trade more with neighboring, friendly, or subject countries is largely inspired by this consideration, and it has been one of the most powerful motive forces behind the policies of regionalism and empire trade….

The second effect of foreign trade from the power standpoint is that it may become a direct source of power. It has often been hopefully pointed out that commerce, considered as a means of obtaining a share in the wealth of another country, can supersede war. But commerce can become an alternative to war also—and this leads to a less optimistic outlook—by providing a method of coercion of its own in the relations between sovereign nations. Economic warfare can take the place of bombardments, economic pressure that of saber rattling. It can indeed be shown that even if war could be eliminated, foreign trade would lead to relationships of dependence and influence between nations. Let us call this the influence effect of foreign trade…Thus the power to interrupt commercial or financial relations with any country, considered as an attribute of national sovereignty, is the root cause of the influence or power position which a country acquires in other countries…..”

—Albert Hirschman, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade, 1945

I was familiar with Hirschman for his “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty” framework, outlined in Hirschman’s 1970 book of that name and mentioned here at The Editors in posts such as “The Talmud on Moving Out of a City to Avoid Taxes,” July 4, 2024, and “Prairie State spending soars,” April 1, 2024, and in a series of posts at our predecessor site FutureOfCapitalism.com, including “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty,” December 2, 2018.

Hirschman’s work on trade, though, only now is getting on my radar screen.

It’s timely, because President Trump himself has been posting to social media on this topic in the early morning hours as the Supreme Court considers a case that could potentially strike down the $4 trillion (over ten years) in tariffs Trump has imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977. “Because of Tariffs, easily and quickly applied, our National Security has been greatly enhanced, and we have become the financially strongest Country, by far, anywhere in the World. Only dark and sinister forces would want to see that end!!!” Trump posted this morning. Trump also posted, “The biggest threat in history to United States National Security would be a negative decision on Tariffs by the U.S. Supreme Court. We would be financially defenseless. Now Europe is going to Tariffs against China, as they already do against others. We would not be allowed to do what others already do!”

A few other sources have pointed to Hirschman’s ideas as an inspiration for the Trump policy.

American Affairs, a small and somewhat obscure Trump-proximate journal of ideas, published an August 2022 piece by Walter M. Hudson headlined “Revisiting Albert O. Hirshman on Trade and Development.” It was a review of a 2021 intellectual biography of Hirschman published by Columbia University Press. Hudson writes:

The unique qualities of Hirschman’s realistic, empirical approach are found in his first book, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (1945), largely ignored when it was first published, though subsequently influential as a proto-geoeconomics text. In it, Hirschman traces how Germany in the 1930s deliberately pursued trade mastery over smaller and weaker states to gain power-based advantages. Nazi Germany wanted to trade with lesser industrialized nations that it could more easily “entangle” into its economy. Whereas developed countries could, with their slew of exports, look elsewhere, developing countries with little more than commodities to export had fewer options. The swifter Germany could entangle these nations into close, or even exclusive, relationships with German manufacturers, the easier it could control them.

This argument about exploitative trade relationships was not, in its basic form, controversial. Many economists, such as Alexander Gerschenkron, saw the Third Reich’s trade practice as something specifically Germanic, as an outgrowth of deep-seated patterns of Teutonic-Prussian aggression. In contrast, Hirschman contends that such motivations could not be so easily reduced to the nation’s predatory history. Rather, he asserts that trade itself is particularly prone to geopolitical manipulation and not simply economic calculation. Indeed, Hirschman further insists that, in the right circumstances and given the right instruments, any nation could act the way Germany did in the 1930s. Trade between countries is not simply about the provision of goods, but about competitive national advantage fraught with both economic and political consequences. Trade is not simply about the goods you trade (the “supply effect”); it is also about your ability to influence whom you trade the goods with (the “influence effect”), in the short and long term. Even if war “could be eliminated, foreign trade would lead to relationships of dependence and influence between nations.”

Hirschman provides statistical data, historical evidence, and Marshallian formulae to demonstrate that none of this is an exclusively German phenomenon. Germany’s motives were impure and its aims ultimately self-destructive—its quest for autarky to support its campaign of conquest led to catastrophe. But that does not invalidate Hirschman’s basic premise: trade between states creates power dynamics that states themselves will exploit.

Two University of Virginia professors, Peter Debaere and Manuela Achilles, have an October 2025 article in a journal called GlobalEurope headlined, “Trade Policy as an Assertion of National Power: Reading Hirschman to Understand the Donald Trump Administration.” They write, “Hirschman’s central insight has stood the test of time: Trade policy can serve as a deliberate instrument of political power even when it runs counter to the economic interests of the country imposing it. In Hirschman’s terms, tariffs and related measures can be wielded strategically to create or exploit international dependency, thereby extending a nation’s political leverage over others.”

Debaere and Achilles go on, “for economist Hirschman, the link between politics and economics was personal. Born in Berlin in 1915 to a Jewish family, he left Germany in 1933, fought in the Spanish Civil War, took part in anti-fascist activities in Italy, and, before emigrating to the United States in 1941, helped Jewish refugees escape from France…His National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade (1945) examines how a power-seeking state can weaponize trade to extend its political influence. The book helps to explain the deeper rationale behind the Trump administration’s bilateral approach. This emerging economic policy is not primarily—if at all—about economics. It is about asserting political power….In his view, sovereign states seek power, which by its very nature is a zero-sum game: One country’s gain is another’s loss. To be sure, free trade (in theory) generates gains from trade for all, as countries specialize and export what they produce relatively cost-efficiently and import what is costlier for them to produce. Yet, trade and specialization also expose nations, making them more vulnerable and dependent on others. For Hirschman, the key question is how states navigate and exploit this interdependence to their own political advantage and to the detriment of others. He doubts that the cherished gains from trade can tame power-hungry nations’ aggression. Predatory behavior is always possible. Sovereign nations can seek to exploit others’ trade exposure to dominate them. In such contexts, economics does not have the last word.”

This is not an endorsement of Trump’s tariffs, either as constitutionally legal or as sensible policy, and it’s also not a prediction of what the Supreme Court will rule. I’ve been asked what I think will happen if the court strikes the tariffs down. Will the stock market soar because of the lower tariff-free prices strengthening consumers and corporate profits? Or will the stock market sag because suddenly there is suddenly a new $4 trillion hole in the federal debt and deficit picture? Maybe the market will respond approvingly to the idea that the U.S. remains a nation based on constitutional rule of law, and that the Supreme Court exists as a check on presidential power. Even if the Court fails to act, nothing is preventing Congress—especially if Democrats take control—from repealing the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, narrowing it, or repealing whatever tariffs Trump has imposed under its authority.

A British newspaper, The Independent, published a short piece about Hirschman in April 2025 headlined, “Is this the secret manual behind Trump’s tough talk on tariffs?” And Gillian Tett had a smart column in the Financial Times, also in April 2025:

Viewed through the lens of mainstream 20th-century economic thinking — be it that of John Maynard Keynes or free-marketeers like Milton Friedman — such tariffs seem strangely self-sabotaging. Indeed, the so-called liberation day declared by Trump smacks of such economic lunacy that it might seem better explained by psychologists than economists. However, I would argue that there is one economist whose work is very relevant in this moment: Albert Hirschman, author of a striking book published in 1945, National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade.

Used copies of Hirschman’s “National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade” are selling for $184 at Amazon, which you don’t need to be a distinguished economist to understand is probably an indication that the book is in some demand.

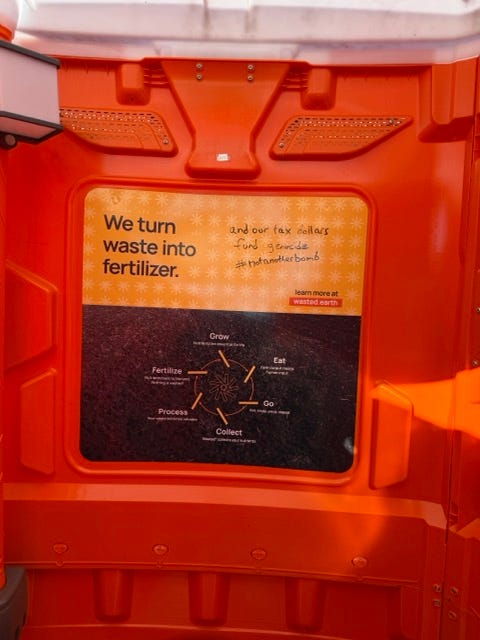

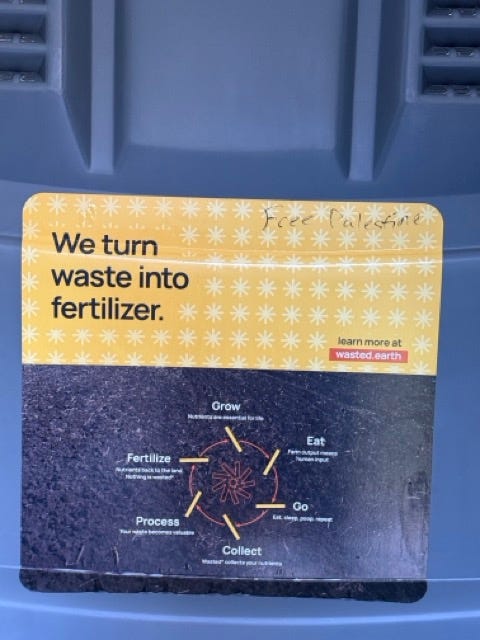

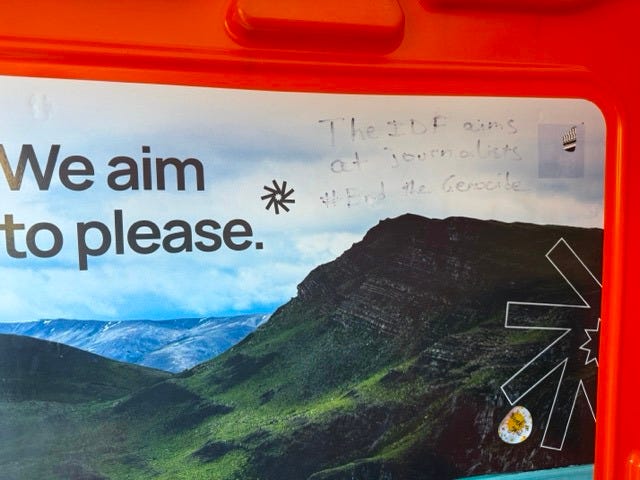

New anti-Israel vandalism attacks at Harvard site: The 281-acre Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University, is one of my favorite spots for a peaceful walk in Boston. Usually the biggest excitement will be lilacs in bloom, a red-tailed hawk overhead, an occasional deer, or, in rare instances, a Harvard sports team training on roller skis.

This morning, unfortunately, I discovered that four restrooms at the site had been vandalized with anti-Israel graffiti.

The Arboretum’s associate director of external relations and communications, Jon Hetman, responded to an inquiry from The Editors about the vandalism with what struck me as a gracious and appropriate response:

Thank you for bringing this to our attention. We deployed staff to remove the graffiti from the portable bathrooms immediately upon receiving your notice. There was some difficulty in removing one of the defaced stickers entirely; we have requested a replacement of the sticker or entire unit from our vendor. In addition, we have reported the incident to the Boston Park Rangers and to Harvard University Police, and our staff will be on the lookout for any further defacement in these facilities in coming weeks.

We appreciate your vigilance and your help as we endeavor to provide a safe and respectful environment at the Arboretum for all visitors. Please don’t hesitate to reach out if you notice anything further or have additional concerns.

I also reported it to the City of Boston, which shares some responsibilities for the area with Harvard, which uses the site for research on biology and environmental science.

The attack on the Arboretum is the latest in a series of property crimes by anti-Israel activists in the Boston area. The vandalism has been directed at both Harvard and non-Harvard targets and has struck in Boston, Brookline, and Cambridge.

Among the other attacks:

A June 15, 2025 attack on the Butcherie, a kosher market in Brookline. The supermarket had a brick with “Free Palestine” written on it thrown through its front plate-glass window. The governor of Massachusetts, Maura Healey, denounced the attack as “deeply concerning and totally unacceptable,” and Brookline Police described it as a hate crime investigation, but no arrests have been announced.

An October 8, 2024 early-morning window-smashing vandalism of University Hall at Harvard together with splashing red paint on the John Harvard statue in Harvard Yard in what was described as an “act of solidarity with the Palestinian resistance.”

Vandalism that I encountered, and took pictures of, in Boston’s Emerald Necklace parks on the morning of May 12, 2025.

On September 9, 2024, at least five painted anti-Israel statements on park walkways, stonework, castings, and a lamppost in Olmsted Park, part of Boston’s famed “Emerald Necklace” of parkland designed by Frederick Law Olmsted.

The Arboretum especially and the Emerald Necklace generally are kept in near-pristine condition, so the situation is basically the only graffiti you see is anti-Israel graffiti. I try not to let this sort of thing bother me, but it’s a little jarring when you go somewhere that you think of as a peaceful refuge and are confronted with these sorts of messages. On the substance of the particular charges contained in the bathroom graffiti, I’ve addressed earlier the Israel-killing-journalists one and the genocide one and free Palestine one. Whatever your view on the war in the Middle East or of Israel or of U.S. foreign policy, though, why not pursue it by electoral politics and organizing rather than through vandalizing or defacing parks, markets, and university buildings and portable restrooms?

Thank you: The Editors is a reader-supported publication that relies on paying customers to sustain its editorial independence. If you know someone who would enjoy or benefit from reading The Editors, please help us grow, and help your friends, family members, and associates understand the world around them, by forwarding this email along with a suggestion that they subscribe today. Or send a gift subscription. If it doesn’t work on mobile, try desktop. Or vice versa. Or ask a tech-savvy youngster to help. Thank you to those of who who have done this recently and thanks in advance to the rest of you.

Debaere and Achilles perpetuate an annoying trend to avoid describing an individual as Jewish. They describe Hirschman as born "to a Jewish family".

This style is very common in Wikipedia, where it is sometimes worded as "born to Jewish parents". The insinuation seem to be that being born Jewish doesn't mean that you should consider yourself Jewish.

It would be interesting to find out where the style started.

Lest anyone be discouraged from purchasing the Hirschman book on trade by the $184 price cited for a used copy, new paperback copies appear to be available on Amazon for $37. There is an interesting account of the origins of the book in the biography of Hirschman by Jeremy Adelman ("Wordly Philosopher") at pages 207-217 and of the reasons it was "almost instantly forgotten" upon its publication in 1945