The Arc of Lieberman

Plus, Steven Pinker on what went wrong at Harvard

If there’s a consensus emerging about Senator Joseph I. Lieberman, who died this week at age 82, it’s that he’s the last of a kind. “We think of Lieberman as one of the last of a magnificent and fast-fading species, the centrist Democrat,” our friends at the New York Sun editorialized. “The kind of Democrat who can’t be found much these days,” the Wall Street Journal editorial called him. “There’s no room in American politics for a centrist like Joe Lieberman anymore,” rued a Facebook post from Seth Gitell, an astute political observer who covered Lieberman as my colleague at the Forward. Lieberman’s death is, as Malcolm Hoenlein put it, “an immeasurable loss” for “the Jewish people, Israel and the United States,” and “no one else will fill this huge void.”

It’s true that with varieties of isolationism on the rise among both Republicans and Democrats, Lieberman’s internationalism and advocacy of a strong national defense will be missed. It’s true that, with the U.S.-Israel relationship under strain and with Israel at war (and America, too, though not all of us realize it) against Iran and its proxies, Lieberman’s moral clarity, analytic intelligence, and communications ability on those issues will be missed. And it’s true that amid concern about extremism, polarization, and bitterness, Lieberman’s moderate centrism, bipartisanship, civility, independence, and good humor will be missed.

Yet burying Democratic centrism along with Joe Lieberman would be an error. That is a message plenty of people would prefer you not hear. The Republicans certainly don’t want to acknowledge there are any non-radical Democrats left. And the progressive Democrats are also happy to declare ideological victory over the Lieberman wing of the party.

My own interest is in the policy substance, not the partisan aspect of it. I think it’s good for America to have sensible people in both major parties. The encouraging thing is that they do exist. If anything, on foreign policy the Democratic Party today is probably in at least somewhat better shape than it was in during the George McGovern era when Lieberman began his political career. Democrats such as Senator Reed of Rhode Island and Jeanne Shaheen of New Hampshire are reliable votes for defense spending. There are pro-Israel Democrats supported by Democratic Majority for Israel—Rep. Ritchie Torres of New York, Senator Fetterman of Pennsylvania, Josh Gottheimer of New Jersey. The February 13, 2024, vote for aid to Ukraine, Israel, and Taiwan was 70 to 29. And with Larry Hogan running for Senate in Maryland and John P. Avlon running for Congress on Long Island, there are more centrists in the pipeline. Do not despair. That’s not to paper over the problems in both parties, just to inject a note of reality, and optimism, amid the morosity.

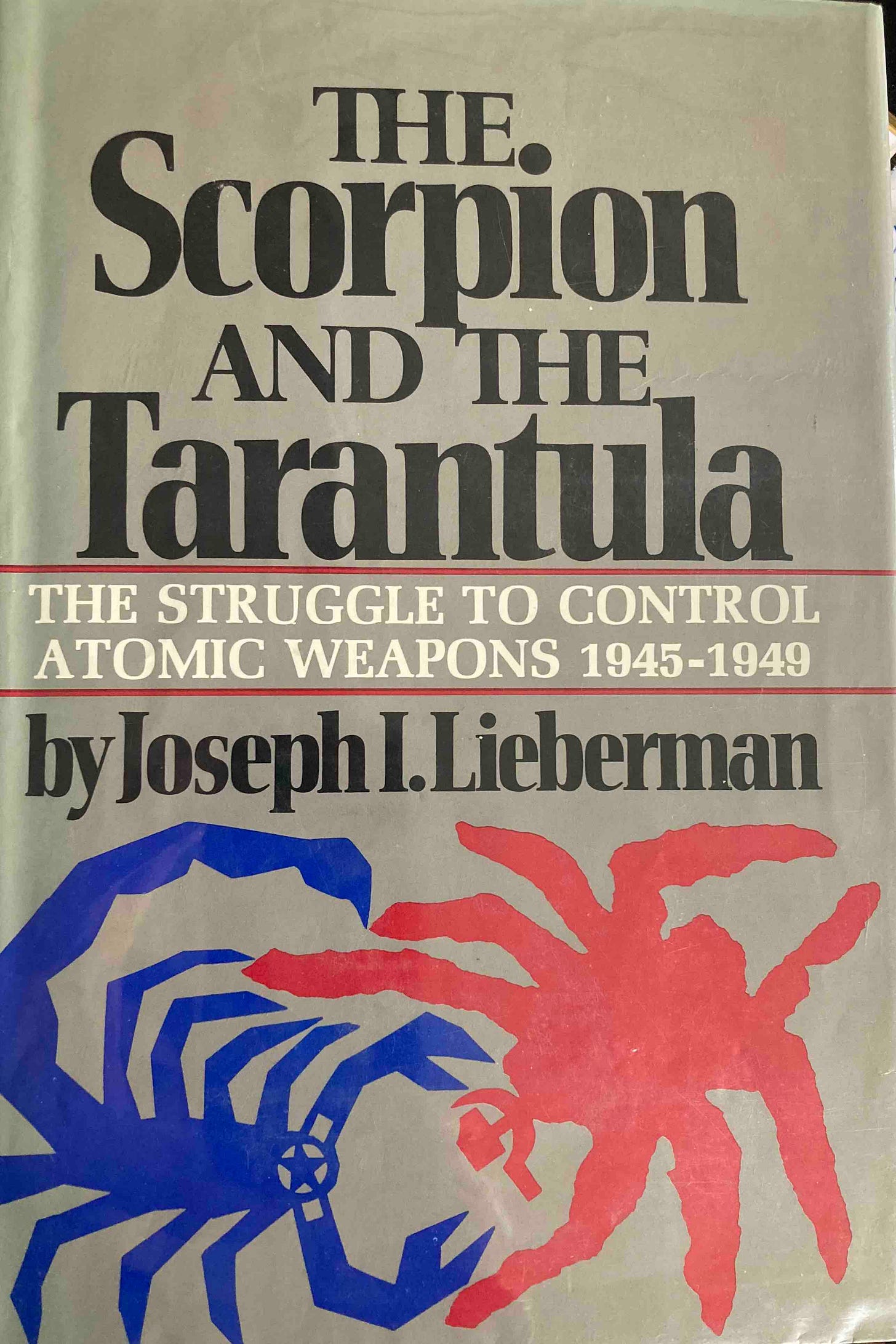

There’s another reason for optimism, too, which is that, as Lieberman’s own story shows, people have a way of moving to the right over time as their idealism comes into contact with reality, as they emerge from universities and encounter the rest of the world. I remembered that as I looked back at my August 30, 2000, Wall Street Journal piece headlined “Joe Lieberman, Radical Historian,” about a little-known, 1970 book by Lieberman, “The Scorpion and the Tarantula,” which the Yale Law graduate wrote in the spirit that the Cold War “is not fundamentally a case of the wicked against the virtuous.” Lieberman, then the Democratic vice presidential nominee, sent me a statement backing away from the book, explaining, that it “certainly does not reflect my thinking about foreign policy or our national security today.” He said, “I became a strong advocate of military readiness and of using our military power when necessary to oppose any such tyranny.” It wouldn’t surprise me to see at least some of today’s left-wing Democrats, especially the young ones on our college campuses, move rightward over time as they come to understand with more accuracy the true nature and aims of our enemies.

Lieberman was guided in his career by his faith. The counterargument to my optimism may be that the decline in faith over the decades makes it less likely that today’s politicians will travel similar political paths. The religious trends, too, though, may change over time, and perhaps more quickly than anyone expects.

Lieberman was a religious enough Jew that he was familiar with the phrase “speedily in our days,” or “bimheira b’yameinu.” I can hear him, as I am sitting here writing this, uttering that phrase, with a twinkle in his eye and a smile on his lips, in his almost William F. Buckley Jr.-esque Yale or Connecticut accent. That is the timeline on which the Jews pray for the messianic era in which the temple will be rebuilt. So the prospect of a religious revival with positive political consequences isn’t necessarily something Lieberman would have found totally improbable. Joe Lieberman is gone, but Joe Lieberman had enough faith in America, and in God, that he wouldn’t have bet that he’d be the last Joe Lieberman. He’d bet on there being many more of them.

Recent work: “Who is that calling the iPhone too expensive?” The real monopolist is the government, not Apple, I argue in my latest New York Sun column. “While the iPhone has gotten better and, for some models, cheaper, the federal government has failed to improve noticeably — while more than doubling in cost.” Check out the full column over at the New York Sun.

More recent work: “Why the New York Times Audience, and Its Editors, Find Peter Beinart so Appealing” is the headline over my latest Algemeiner column. Check the full column out over there if you’d like.

Thank You!: Today’s column is an example of what readers are saying about The Editors: “it’s objective & uncompromising” “Your writing is thought provoking, and what more could one expect or hope for?” “I always learn something new” “Because Ira Stoll’s reporting concerns highly significant but generally under reported events--and his analyses are elegant despite a sharp edge” “Reading your articles is a highlight of my day.” Thanks to every one of you for being a reader. Please consider helping us grow by becoming a paid subscriber (which will also enable you to read the remainder of today’s newsletter).

Harvard update: Steven Pinker, one of five “co-presidents” of the Harvard Council on Academic Freedom and a professor of psychology at Harvard, gives an interview (“What Went Wrong at Harvard”) to Reason’s Nick Gillespie. Pinker: “Harvard itself is in a kind of crisis by its own standards, which is to say that donations are down…. And applications are down. It's become a national joke. I have a collection of memes and headlines and bumper stickers, like ‘My son didn't get into Harvard.’ An editorial cartoon of a corporate guy saying, ‘This guy has a stellar resume, straight A's, top scores, didn't go to Harvard.’ The reputation, which is a huge resource that Harvard has drawn on, is threatened. And when it's threatened, a lot of Harvard's comparative advantage will also be threatened. Harvard has a lot of money, but it also can to some extent coast on its reputation…. The fact that it does have an outsized reputation means that it has a certain cushion. Not every department has to compete to be the best in the country because students will come, graduate students will come, donors will give.”

On the ideological conformity problem: “If you just define viewpoint by the conventional left-right political spectrum, then things look pretty grim because according to at least a survey of The [Harvard] Crimson, 3 percent of Harvard faculty identify themselves as conservative. And out of those 3 percent, a lot of them are in their 90s, so we know where that's going…. The question is, how do you rescue programs, universities, departments, fields that become self-referential echo chambers?”

An example: “I was on a hiring committee for another department at Harvard, not psychology. There was an excellent candidate, who was by any standards, including his own, a political liberal, but he had some heterodox positions. He was opposed to affirmative action, for example. The department chair said, ‘We can’t hire him. He’s an extreme right-winger,’ meaning he had criticisms of affirmative action. You often think of academia as being at the Left Pole. North Pole is the spot from which all directions are south. The Left Pole is the hypothetical position from which all directions are right.”

Elsewehere on the Harvard front, a plaintiff in one of the lawsuits against Harvard, Shabbos Kestenbaum, reports that the Harvard Law School student government plans a “secretive” and “rushed” vote on a resolution calling on Harvard to “divest completely from weapons manufacturers, firms, academic programs, corporations, and all other institutions that aid the ongoing illegal occupation of Palestine and genocide of the Palestinians.”

A lot of people’s big hope to rescue Harvard is John Manning, a former clerk to Judge Robert Bork and Justice Antonin Scalia who was recently elevated from Harvard Law School dean to interim provost of the entire university. Manning may help with the viewpoint diversity problem outlined by Pinker above. Let’s hope so. Yet Harvard Law School has certainly not avoided some of the most factually unmoored Israel-bashing, suggesting that “Manning-as-savior” may be something of a fantasy, or at least a very long-term route toward a fix at Harvard.

Thank you!: If you value what you are reading here, please consider forwarding this email to a friend with a suggestion that they subscribe.

We need more leaders like Sen. Lieberman who have a genuine faith and fear of God guided by a true moral compass of absolute truths and not relativism.

Re Harvard: In 1982 Harvard sent interviewers to my high school (formerly known as Boston Latin School, sarcasm). Interviewer asked me latest book I’ve read. I replied Machiavelli’s Prince. She asked if President Reagan was Machiavellian. I said no. Interview went south from there. My application was doomed.