Republicans Against “Opportunity”

Plus, who is teaching Harvard’s “meritless” courses?

A battle is raging within the Republican Party and within the center-right generally in America between traditional free-market economics types and those who want to replace that with something else that is vaguely defined but usually involves higher taxes and more government involvement. In the “replace that with something else” camp is a guy called Oren Cass who is effective at outreach to the media and to certain Republican senators, particularly Rubio and Vance. I’ve written about Cass and his “American Compass” outfit previously over at FutureOfCapitalism, a predecessor site to The Editors.

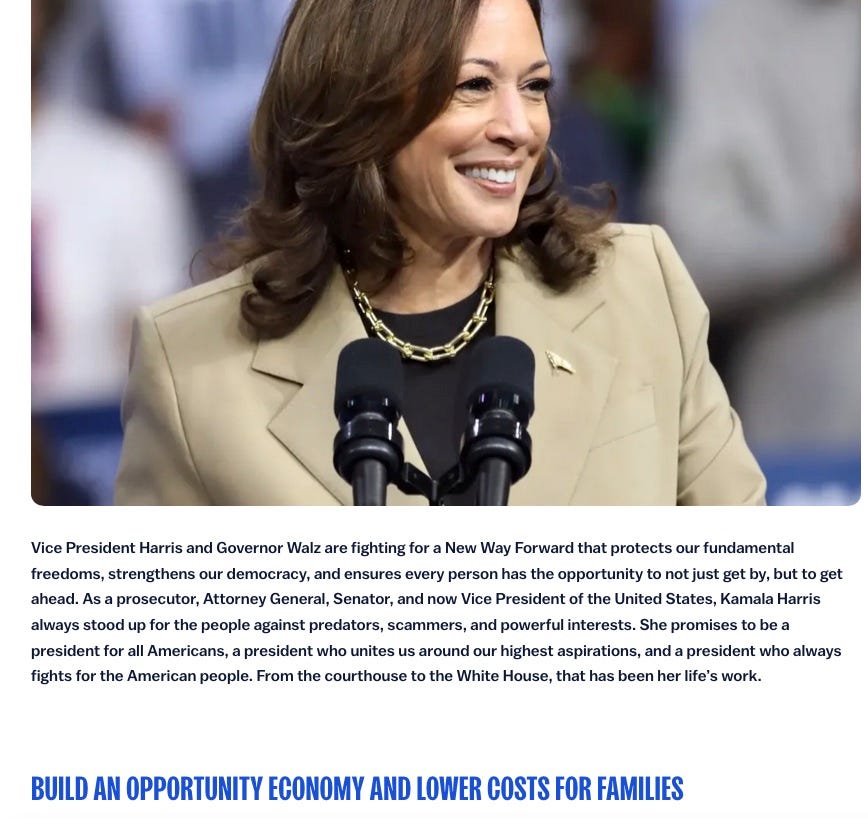

Cass now has a newish Substack called Understanding America. He has a new piece out there, provocatively, attacking Kamala Harris for talking about an “Opportunity Economy.” Cass writes:

the obsession in our political rhetoric with “opportunity” is misplaced. Much more important than “opportunity” and “mobility” is “stability” and “security.”

In support of that claim Cass marshals a focus group and a Pew poll fielded in 2014.

Cass insists he’s not totally against opportunity, but he warns that it’s risky: “Before getting excited about ‘a chance,’ it’s important to know the odds.” He says America shouldn’t overemphasize it: “We can value opportunity and mobility without always defining them as the top priority and most worthy aspiration, making their shortcomings the key challenge, and using them as the organizing principle for our politics.”

It’s hard to convey in words the level of exasperation that Cass’s argument generates from me in terms of a gut reaction. You might sum it up as “oy!” It’s true that people have different tolerances for risk and different levels of ambition, based on everything from life experience to family and religious background. Yet Cass seems to ignore that one of the things that has always made America special compared to the rest of the world is the opportunity available here. People who valued stability over mobility might not have made the decision to immigrate to America in the first place. Plenty of European countries have cushy welfare safety nets, but fewer great fortunes and world-changing companies are created there, there’s less dynamism, and there’s lower economic growth.

Aside from the questions of national character and comparative political economy, Cass’s analysis takes public opinion as fixed. Yes, soon after the 2008 economic crisis, which featured foreclosures and job losses, security and safety might be more salient than opportunity and mobility. But part of political leadership might involve cultivating risk-tolerance and celebrating entrepreneurship, rather than simply altering the agenda to appeal to a nation of civil servants and factory workers with an expectation of lifetime job tenure. Part of politics is reminding Americans that this is a land of opportunity, rather than a place where the government dispenses security and stability to passive recipients.

Cass blames “our political elite” for what he views as the misguided emphasis on opportunity. “The view among those who have dedicated their lives to achieving and exercising power from society’s apex tends to be a peculiar one, even as it gets broadcast from that apex as the norm,” he writes. It’s not clear exactly about whom he is talking, but it could be that some of those people do prefer the emphasis on opportunity. Perhaps they have the wit to realize they are the ones who are going to be taxed and regulated more in pursuit of “stability.”

Anyway, one can debate the abstract preferences between stability and opportunity from now until tomorrow, but typically they are translated into concrete tax, spending, and regulatory policies. Those policies are sometimes billed as win-win or rising-tide-lifts-all-boats, but they sometimes turn out, also, to involve more zero-sum tradeoffs.

I’m not a huge Harris booster by any means, but I’m happy to see her at least rhetorically embracing “opportunity” language. Republicans who spurn the language and the policies while chasing votes may find themselves punished when voters eventually realize that emphasizing safety over opportunity doesn’t result in much safety either. Ask anyone whose family came to America from a communist or socialist country.

Harvard’s ‘Meritless’ Courses: The Harvard Salient, a conservative student publication, reports that “While receiving a legitimate humanistic education at Harvard is still possible, the number of meritless courses has made separating the wheat from chaff increasingly challenging.” It proceeds to list 20 actual, non-parody offerings from the Harvard course catalog with titles such as “Street Dance Activism: Co-choreographic Praxis as Activism” and “Queer Interventions in Latinx Studies.”

I’m not passing any judgment myself here on whether those courses are worth a student’s time or a parent’s money. But I thought it’d be interesting to take the analysis a step further and ask, who is teaching those classes? Eighteen of the classes have named instructors. Here are the titles of the teachers:

One class probably isn’t actually offered anymore, as the instructor listed is a tenured professor who abruptly retired without emeritus status after sexual misconduct complaints.

Lecturer on education

Richard B. Wolf Associate Professor of Women, Gender, and Sexuality

Associate Professor of Classics

Postdoctoral Fellow in the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History

Lecturer in Native American and Indigenous Studies

Lecturer in History and Literature

Associate Professor of English

Assistant Professor of Roman Catholic Theological Studies

Professor of the Practice in Media and Activism

Director of Studies and Associate Senior Lecturer in the Committee on Degrees in History & Literature, and a Faculty Associate at the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies at Harvard University.

Adjunct Lecturer on Education

Assistant Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures, Harvard University

Lecturer in Latinx Studies

Lecturer on Education

Adjunct Lecturer in Public Policy

Instructor in Medicine, Part-time

Visiting Assistant Professor of Women’s Studies and Theology

Lecturer on Somatic Performance and Contemporary Global Performance, Theater, Dance & Media

There’s not a single full tenured professor on the list. Even junior ladder faculty—the five with “assistant” or “associate” titles but not “visiting”—are far outnumbered by the lecturers, fellows, instructors, and professors of the practice.

You could say that shows how ethnic and gender studies have been marginalized or underinvested in at Harvard, or you could say it shows how Harvard is farming out the teaching duties to lower-paid staff who are less distinguished in the academic pecking order and who haven’t yet met the qualifications to become a tenured full Harvard professor.

Students are often unaware of or unattuned to these subtle status distinctions, figuring the grownup teaching the course is functionally a Harvard faculty member, regardless of whether the person’s actual title is professor, professor of the practice, or “lecturer.” Harvard administrators who oversee the tenure process can congratulate themselves for upholding supposedly rigorous standards—no, we aren’t going to promote that professor of “activism.” But plenty of Harvard courses are taught to plenty of Harvard students by teachers who haven’t met those standards and who likely never will. These teachers aren’t necessarily inferior for a student to learn from—Arthur Brooks is a professor of the practice, and Jason Furman is a professor of the practice, and I wouldn’t discourage anyone who had the chance to learn from either one of them—but it’s a different model than the classic world-class-researcher Harvard professor.

The lack of tenure protection, lower compensation, and uncertain job security for lecturers or adjunct faculty can sometimes translate into alienation and more left-wing politics. It’s something that the full Harvard professors who care about the institution worry about, though they also realize that shifting more of the teaching load onto people like themselves would be expensive, both in terms of their own time and in terms of hiring more senior faculty, who are more expensive than lecturers.

Harvard backs Harris: Under the headline “featured events,” the Harvard-central–administration-published Harvard Gazette emails out a link to a “Democracy ’24 town hall” featuring Laurence Tribe and Robert Shrum.

Shrum and Tribe are both liberal Democrats, so I checked the calendar of these town halls to see the political tilt. Another event features “Harris Campaign Senior Advisor on Reproductive Rights” and “National Co-Chair, Women for Harris.” That’s democracy, Harvard style, when the town hall events feature two Harris campaign officials and no Trump campaign officials. Democracy is in such danger that it’d be too risky to allow both major candidates to have a voice, right?

I wrote to the contact form listed on the event to see whether there were any pro-Trump speakers scheduled, what corporate entity is hosting the event series, and whether it was a partisan anti-Trump political effort. I got no reply. Anyway, it’d be interesting to test whether the Harvard Gazette would mail out as a “featured event” a promotional link to a zoom series featuring events that include two Trump campaign advisers and zero Harris campaign advisers. I highly doubt it.

Harvard can announce all the institutional neutrality and institutional voice policies it wants, but so long as the faculty and students are 95 percent or more left-wing, and so long as the central-administration-published Gazette is promoting this sort of stuff, people will draw their own conclusions.

Thank you: We are participating in the opportunity economy here at The Editors. If you can afford the $8 a month or $80 a year, please pitch in to defend opportunity and mobility, keep an eye on Harvard and the higher education, sustain our growth, and ensure your continued complete access.

And if you can think of someone else who’d enjoy or learn from this newsletter, please share this.

Turn the Harvard campus into affordable low-rise garden apartments.