New Data Detail Who Is Backing Zohran Mamdani for Mayor

Plus, MIT economists on Boston Latin School’s value-add; can private sector replace the Bureau of Labor Statistics?

In today’s newsletter:

An update on Israel-hating socialist Zohran Mamdani’s campaign for mayor of New York, including two recent polls, a thread from a campaign operative with granular demographic data, and Senator Elizabeth Warren wading in to endorse Mamdani.

Do we really need the Bureau of Labor Statistics? Instead of just appointing a different director, should Trump just ask Congress to shut that bureaucracy down and let the private sector and other government agencies fill in the gap?

And, in our regular Monday “NBER Monday” feature, we look at a new working paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research. In it, two MIT economists review the effect of being admitted to Boston Latin School, a competitive public “exam school.” An earlier paper by one of the authors suggested parents may be operating under an “elite illusion,” mistakenly believing in value-added that didn’t exist. But the new paper, which takes a wider view, says maybe the parents aren’t quite so deluded.

New data offer additional insight into precisely who is powering the campaign of Israel-hating socialist Zohran Mamdani to be mayor of New York.

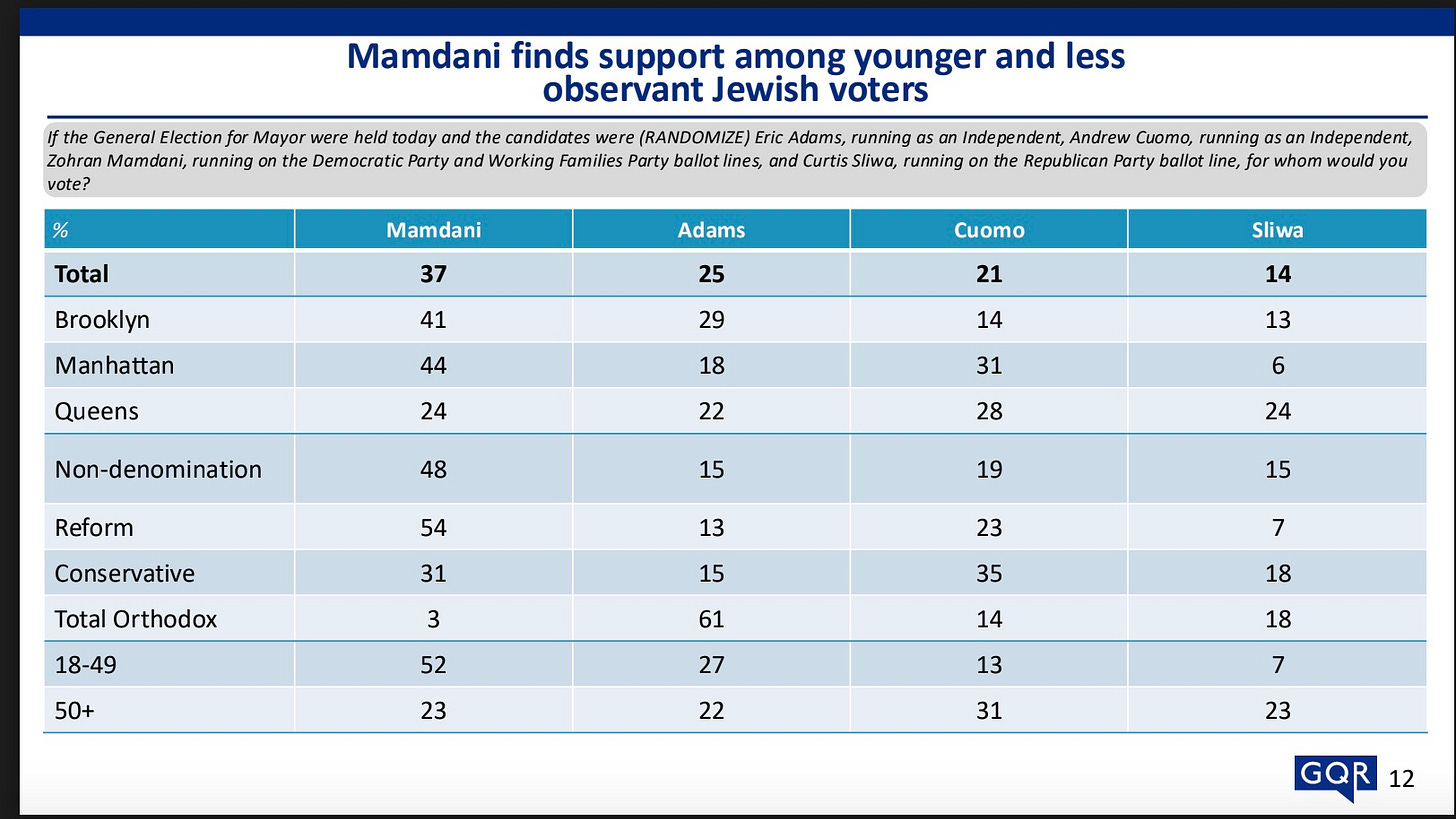

The first information comes from a survey by GQR of 800 registered Jewish voters in New York City. It was conducted for the New York Solidarity Network, which opposes Mamdani. It was fielded July 15 to 24, 2025. Here’s the slide with the key findings, showing Mamdani’s support is far stronger among younger and less traditionally religiously observant voters, and weaker among older and more traditionally religiously observant voters:

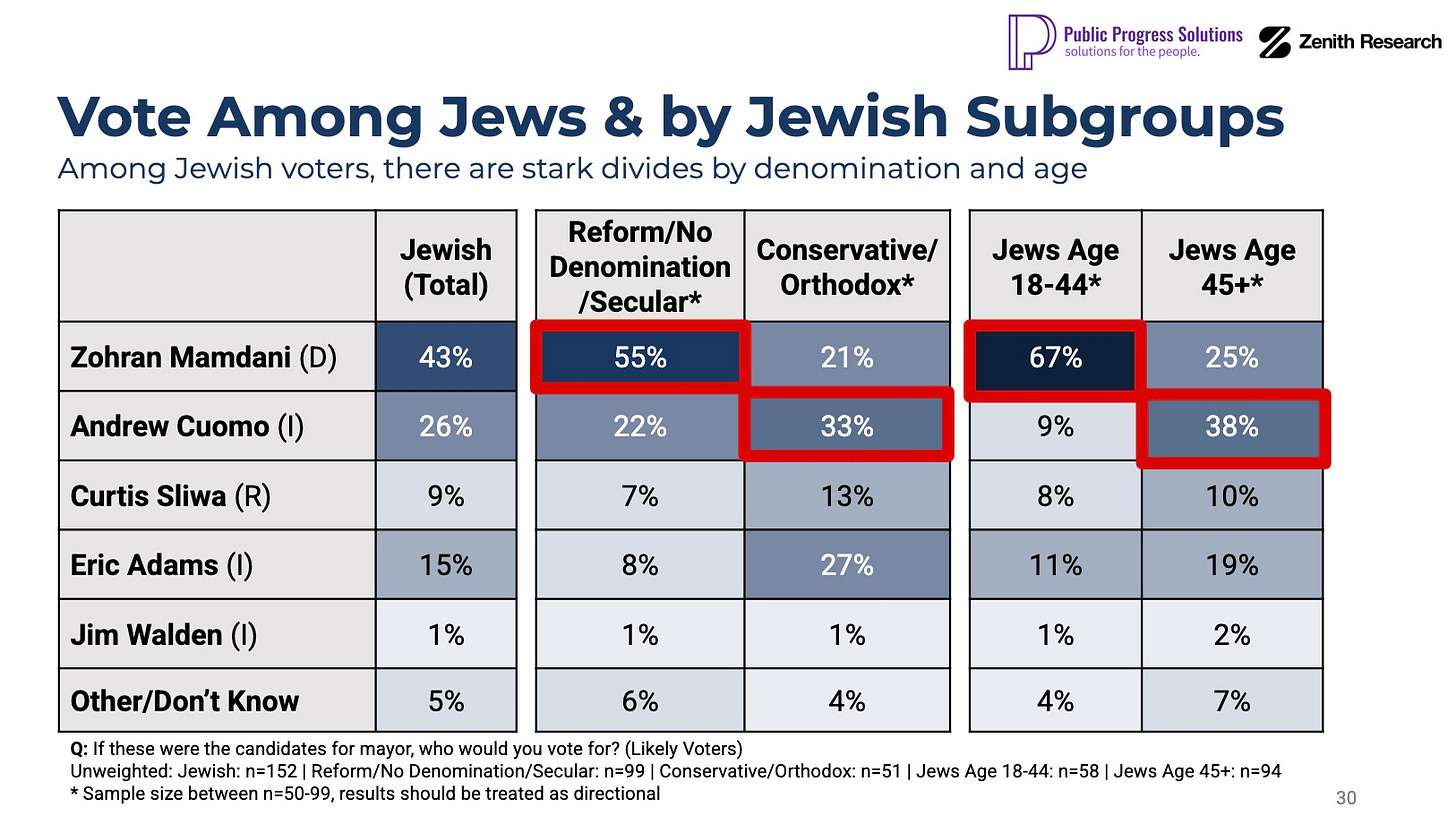

The second set of information comes from a different survey, fielded July 16-24, 2025, with a Verasight sample conducted by Zenith Research and Public Progress Solutions. That research included both registered voters and likely voters, and fewer Jewish voters (so not all the findings are statistically significant, but I’m mentioning it anyway because it tracks with the other poll). Here’s a slide that basically confirms the GQR finding:

The third set of information is a thread on X by “Aaron from Queens,” who identifies himself as a socialist City University of New York law student who helped to target voters for Mamdani in the primary election. He says they aimed for “Muslim and South Asian voters,” “rent-stabilized tenants,” including microtargeted demographics such as “Muslims in the Shore Haven Apartments in Bath Beach” and “Afghanis in Kew Gardens Hills,” “Bangladeshis,” and Pakistanis in Brighton Beach.

I can hear the sophisticated readers out there saying okay, it’s not exactly a stunning surprise to discover that the young and Muslim voters backed Mamdani and the older Orthodox Jews aren’t big fans of his. Okay, fair enough, but it’s still nice to have data that supports the perception. I’m the farthest thing from a demographic determinist. But you don’t have to be Trump aide Stephen Miller to observe that the trends in New York over the past few decades—retired municipal workers moving south to Florida or other lower-cost states, Jewish population growth shifting to New Jersey and Long Island, and the population increases in the city being driven by recent international immigration—are finding a reflection in the election results.

Senator Warren was in New York today to endorse Mamdani. David Faber on CNBC did a near-heroic job of arguing with her that the tax-the-rich approach she and Mamdani support would accelerate the flight from the city of talent and jobs. (It was so near-heroic that Fox News even wrote it up.) In an article, Warren praises Mamdani for being “willing to stand up to ultra-powerful special interests,” such as “billionaire real estate moguls” and “the ultra-rich and giant corporations” and “big law firms, commercial brokerages, and big real estate developers” and “Wall Street executives.” This is the Warren version of Trump blaming illegal immigrants for problems—a politics that finds villains to demonize and scapegoat. Warren and Mamdani deserve each other.

Can private-sector or tax data replace the Bureau of Labor Statistics? President Trump has the “norms” people all worked up after firing the director of the Bureau of Labor Statistics following some revisions to the monthly job statistics.

Nate Silver wrote a version of what I was thinking before I did. He says,

If the government’s jobs data is considered biased or unreliable, Wall Street will have other places to look. ADP reports figures on private payrolls, for instance. (And it also tells a bearish story: ADP showed a net loss of jobs in June, for instance.) Meanwhile, Gallup once tracked employment numbers on a weekly basis based on its large-scale surveys and could resume that effort. Or investment banks like Goldman Sachs might conclude they could have a competitive edge by tracking their own economic data.

However, this data is likely to be lower quality, because private organizations usually have lower response rates to surveys than the government does. And no longer having any reliable “ground truth” for major American economic data series will create more uncertainty for businesses and investors overall, which will discourage the sort of healthy risk-taking that often fuels job growth.

I’m more optimistic than Silver is about the ability of the private sector to generate this data, either on its own or by compiling data from other government sources. But I’m probably in the minority in that regard. The New York Times today quotes “Alberto Cavallo, a Harvard economist who developed one of the most widely used private inflation indexes in Argentina”:

“Private alternatives can complement official statistics, but they are not a substitute,” Mr. Cavallo wrote in an email. “Government agencies have the resources and scale to conduct nationwide surveys — something no private initiative can fully replicate.”

Recently, Mr. Cavallo has been publishing data on consumer prices in the United States, which has shown the impact of Mr. Trump’s tariffs more quickly than the government’s data. But while such real-time sources are valuable, they don’t carry the “institutional credibility” of government data.

What’s available? There’s the ADP National Employment Report “in collaboration with Stanford Digital Economy Lab” and Paychex, another payroll processor, also releases jobs and wage data. Treasury has payroll withholding tax data, though the danger there is that the more one relies on tax data for anything other than collecting taxes, the greater the risk of data security breaches. States have unemployment claim data and their own state-by-state payroll tax collections. Everyone’s been pointing to the ADP data as proof that the BLS data was not, as Trump claims, “rigged.”

The BLS began its first monthly studies of employment and payrolls in 1915. America somehow managed to get along without it from 1776 to 1915. The dispute has echoes of the fight over Federal Reserve independence, with the Ph.D economists stressing the importance of impartiality in the general context of declining popular trust in elite institutions. The nature of work has changed somewhat because of the gig economy.

One analogy might be weather forecasting, where the energy trading firms hire their own meteorologists rather than relying exclusively on the National Weather Service. Another might be baseball or other sports, where teams and gamblers pay for access to detailed data. Medical and health researchers are always looking for data to analyze to detect patterns, and it starts to get complicated when you ask whether the patients have consented to the use of the data for the researcher’s purpose (see “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks”). Is there something special about employment data that makes the federal government uniquely capable of tracking it? Probably not. One complaint is that establishments don’t respond to the survey. I think at one point I was in that survey, and filling it out was an uncompensated time drain. Sometimes researchers can get better response rates by compensating survey participants for the time they take to fill out the survey.

In the private sector, if your data is unreliable or your collection methods are not keeping up with the times, it’s harder to get people to pay for it. In the government, those accountability mechanisms are less consistent. BLS has about 500 people working on employment statistics, at a cost to the taxpayers of about $300 million a year. One possible move would be for Trump, or his OMB director, to say to Bloomberg or Evercore ISI or the Elias Sports Bureau or LinkedIn or ADP or McKinsey or anyone else who wants to bid for the job, hey, we’re going to hire three companies at $50 million a year each to be the Hertz, Avis, and Budget of the employment statistics, and we’ll keep the BLS going with a skeleton crew of the best statisticians for another $50 million, and we’ll run that experiment for three years and see who does the best job of producing useful and accurate data. Try something new and get the private sector involved. See how it works. For some large employers, payroll data could even become a new revenue stream. We’ll give you realtime access to our payroll data, but you’re going to have to pay us for it. (Matt Levine might worry that this approach would create opportunities for securities fraud, but if the employment data is as crucially important as Trump and all the people worried about Trump now agree that it is, why not put a price on it?)

Anyway, at least thinking this way breaks free of the dichotomy between “Trump is Stalin undermining the institutions” and “the deep state is sabotaging Trump.” That dichotomy seems to dominate so much of the discourse these days. A different approach would be to ask whether everything the federal government is doing must be done by the federal government, at current spending levels, or whether it could be done cheaper or better by the private sector. In some cases it may be possible to empirically test that so that rather than speculating we can find out. Perhaps employment statistics is one of those areas.

NBER Monday: MIT Economists report on Boston Latin School. A landmark paper on exam schools such as Boston Latin School, Stuyvesant High School, and Bronx Science was published as an NBER working paper in 2011 and headlined “The Elite Illusion: Achievement Effects at Boston and New York Exam Schools.” It was by Atila Abdulkadiroglu, Joshua D. Angrist and Parag A. Pathak. Angrist later won a Nobel prize. As the abstract put it, “Our estimates show little effect of exam school offers on most students' achievement….the intense competition for exam school seats does not appear to be justified by improved learning for a broad set of students.”

Now Pathak, who is at MIT, has gone back and, with a new co-author, Glenn Ellison of MIT, taken another look at a wider set of data and come up with a somewhat revised and fuller view of the story. In a working paper released today with the pareve headline, “Optimal School System and Curriculum Design: Theory and Evidence” (you can tell from the bland headline, alas, that Charlie Radin has retired from NBER), Pathak revisits the issue.

Pathak and Ellison write, “We analyze seventeen cohorts of students who applied to BLS for 7th-grade admission. Our outcome measures include detailed data on student performance: scores for each individual question on the Grade 10 MCAS (Massachusetts’ mandatory high school graduation exam during our sample period), scores on both PSAT and SAT exams, AP exam results, and comprehensive college trajectory data including enrollment, persistence, and graduation.”

Their first result confirms the Abdulkadiroglu, Joshua Angrist and Pathak finding “that students just above the BLS admission cutoff show no overall improvement on Grade 10 MCAS scores compared to students just below the cutoff.”

Yet they also find that “BLS admission increases performance on SAT English” and that “admission increases measures of both AP test participation and performance.”

They write that, “These findings collectively…demonstrate that while BLS has no effect on MCAS scores, it does impact more advanced academic outcomes.”

The “elite illusion” of the earlier paper may not have been such an illusion, after all, and the high-scoring students (and their parents) who prefer BLS to the alternative choices may be pretty sophisticated, after all.

This was my first look at this paper, though I’ve seen Pathak present other research elsewhere. Had I been asked to comment on it, I’d have suggested that he avoid the “learning styles” terminology that has elsewhere been debunked. Aside from that, it’s a nifty paper, and, as a happy recent BLS parent myself, and a fairly sophisticated consumer of education, it’s nice to have the MIT economist validation for something that I already knew. It’s like having two polls to show that older and more religious Jews are not big Zohran Mamdani fans. Even if you knew it already, the empirical support is good to have.

And aside from the substance, this is a good case study of how social science works. Good social scientists like Parag A. Pathak go back 14 years later and revisit old findings and modify them on the basis of new findings. It’s a good reason to treat all social science findings with a certain amount of skeptical reserve inherent in the knowledge of the possibility that they might eventually be revised with more data or new analytical frameworks. Bad social scientists (and there are plenty) lack the confidence to do this revisiting, and instead wind up wedded to old results even when new work casts those results in doubt.

This is a live political issue, as the exam schools, despite being beloved by parents, students, and alumni, are under constant political attack from those who see them, along with meritocracy generally, as racist or otherwise inequitable. The old finding that the schools don’t add value on standardized achievement was frequently cited by the exam school opponents. At the risk of instrumentalizing the research, it’ll be useful in the political fights over the schools’ continued existence and their admissions policies to have this new evidence on how they affect outcomes.

Thank you: The Editors is a reader-supported publication. If you are learning things here that you are not getting elsewhere, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. Paid subscribers have full access to all the content and are helping to sustain our growth and editorial independence. Thanks to those who have already pitched in, at a price of as little as $1.54 a week. The paying customers are what make my job possible, whether the federal government counts it or not. If you have trouble making it work on a phone, try a desktop, or if you have trouble on a desktop, try a phone. Or ask some youngster (hopefully not a Mamdani voter) to give you a hand.

Lured me back in with the Boston Latin reference. I am going off memory with the original study that I thought demonstrated limited grasp of how the exam school thing works in Boston. The big difference with BLS versus Stuyvesant is that there weren't then (and even more so today) enough high quality performers to fill a class of 400 such that a study comparing the bottom tier of kids at BLS is simply studying a group of well off underperformers who had the benefit of test prep (and/or inflated parochial school grades). They are the kids the NAACP rightly complains about (yet then failed to create a new system that bumped the undeserving). That 20-40% of kids, those that were over-rated from the outset, do little upon arrival to distinguish themselves from those that weren't admitted. They cheat, take the easiest classes and head off to some open enrollment college. Utilizing them to study whether the exam schools work is like a study of the bottom NBA draft picks in the old days when they had 12 rounds (today there are 2 rounds) and the Celtics would draft friends of the owner's dentist in the late rounds because there weren't enough talented players to make 12 picks. If you studied the undrafted versus the bottom draft picks you would find no difference.