Made-in-America Is Making a Comeback

Plus, the downside of the Schanzer-Stephens plan for Gaza

From giant mass-market retailers to niche high-end haberdashers, “made in America” is making a comeback in communications with consumers.

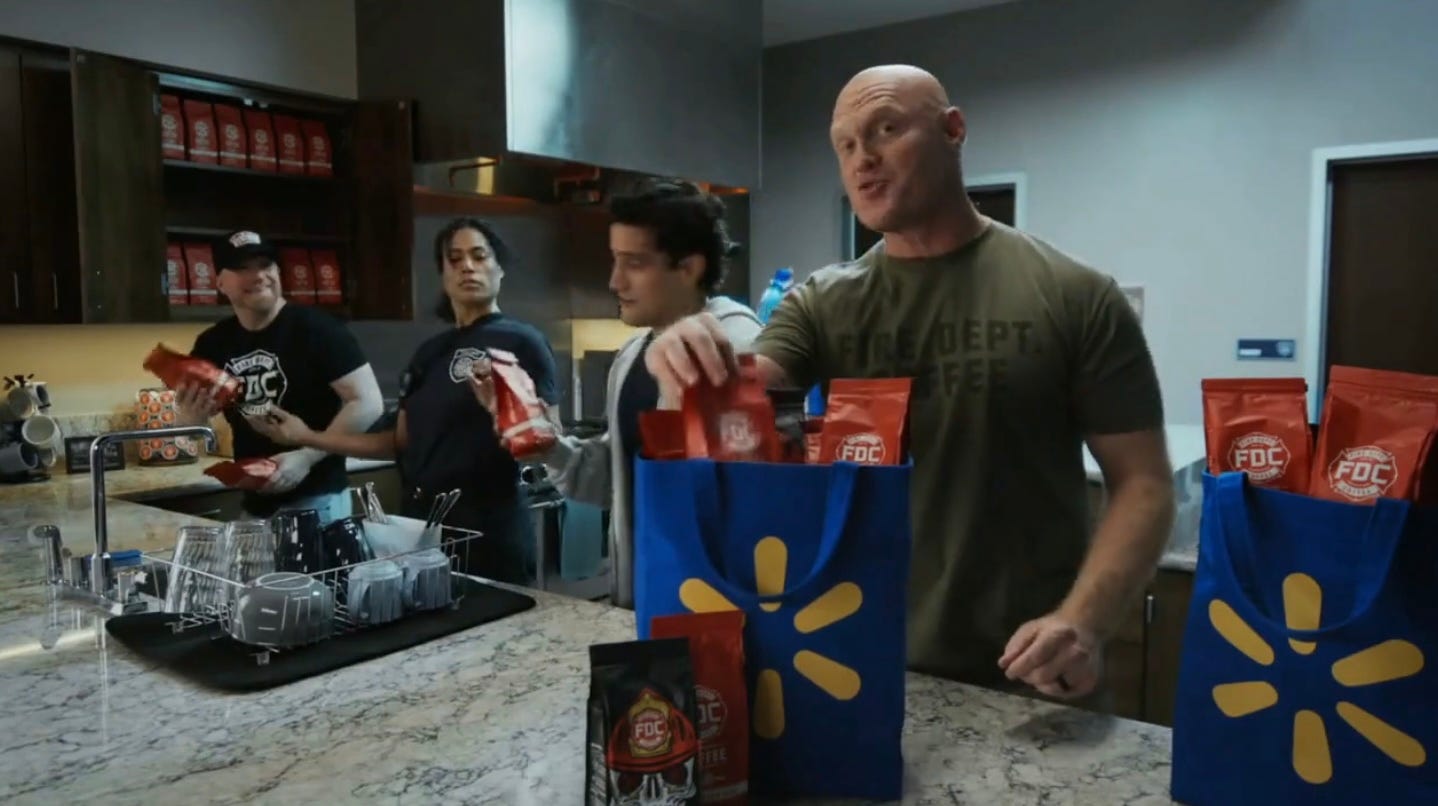

Walmart is running a television commercial featuring Fire Department Coffee, a veteran-owned business founded in Rockford, Illinois. “Most of what Walmart spends goes to products made, grown, or assembled right here in the U.S. so we can invest back into our community,” the commercial says, describing Fire Department Coffee as “a mighty fine American business.” A Fire Department Coffee press release says, “We connected with Walmart through their Open Call initiative, a program designed to support U.S.-made, grown, or assembled products.”

At a smaller scale than Walmart, if there is a men’s clothing brand right that is hot right now it is Buck Mason. The Wall Street Journal wrote about it on July 24 in a piece reporting that its “yearly growth has steadied to between 50% and 100%, with annual sales over $100 million.” A Journal headline said, “By reworking classics and being ‘relentless on quality for value,’ Buck Mason has emerged as the next big brand for just about every kind of guy.” Not mentioned by the Journal, but significant: Go to the Buck Mason home page and the top navigation bar looks like this:

There’s “men,” “women,” and “made in the USA” an acknowledgement that, first, it’s even feasible in 2025 to make clothing in the USA and second, that there are customers out there who are interested in buying it. “We don’t just design clothes; we make them. Buck Mason Knitting Mills allows us to manufacture entirely domestic, American-made products,” the website says. “Farms in California, Texas, and Georgia provide the premium cotton we use. From cotton grown and spun in America to our new mill in Mohnton, Pennsylvania, every step of the Buck Mason Knitting Mills process is domestic. That means quality control, but so much more. It means jobs, dignity, and pride.”

Even J. Press, the Ivy League preppy purveyor of hook-vented natural shouldered suits and “Shaggy Dog” sweaters, now has its website sorted with a “made in America” option, which I had not noticed in the past. That retailer has been Japanese-owned for quite some time.

Sure, these are just three anecdotes, not government data about manufacturing output. An open question is whether “jobs, dignity, and pride” or “invest back into our community” will be worth, for American consumers, the higher prices that sometimes apply to American-made products. Maybe some customers will be proud of products made in Canada or Indonesia or England or Italy or Mexico, and “invest” the money they save from the lower prices in other American goods or services that are less easily imported from abroad. That might even be better for America, on a net basis.

But to understand what’s happening in America, you need to get beyond the academic economists and the legacy media journalists reliant on the academic economists, and watch some of the cultural signals. There are lots of challenges to bringing back American manufacturing, from the academic economists confidently predicting that it won’t happen and that it would be a mistake to try, to the more practical difficulties of finding workers who will come to work consistently. Yet there are indications that consumers have some appetite for it. And generally in America, consumers get what they want.

Tariffs may interact with that desire by evening out some of the price differentials. But this is not primarily a tariff or trade-barrier story, it’s something else—patriotism, nationalism, the public mood, maybe some anti-China or anti-Mexico sentiment. It’s a trend worth keeping an eye on.

The downside of the Schanzer-Stephens plan for Gaza: Bret Stephens today (“Where Can Gaza Go From Here?”) and Jonathan Schanzer in Commentary (“A Third-Way Endgame for Israel in Gaza,” July 26) both advise that rather than going in and taking over the remaining 25 percent of Gaza, Israel basically surround those areas, issue demands, and allow humanitarian aid but not reconstruction.

As Stephens puts it, “there should be no reconstruction aid for Gaza until Hamas releases the hostages and agrees to disarm. Food and medicine, yes — in abundance. Concrete and rebar, no — not so long as it might be used to rebuild the territory’s terror tunnels. It’s time for Hamas to feel the brunt of pressure, most of all from Gazans themselves, for the ruins they created.”

Or as Schanzer puts it, “Living in squalor with no prospects for reconstruction is bound to push the Gaza population to the point of desperation. And while some of the Gazans’ anger will remain focused on Israel, Hamas’s refusal to meet the terms of a cease-fire that could end their nightmare will not sit well. Eventually, the people of Gaza will want to voice their frustration, and perhaps even act on it.”

Schanzer acknowledges one downside: “First and foremost, allowing the hostages to remain in Hamas custody puts them in greater peril.”

It’s possible that the Stephens-Schanzer approach could work. It certainly has the advantage of requiring fewer Israeli troops, and probably fewer Israeli casualties, than a full-scale invasion.

But it’s also possible the Stephens-Schanzer approach could backfire. While Gazan “desperation” and “squalor” might generate internal pressure in Gaza against Hamas, it could also generate international pressure against Israel that would make it harder to achieve the twin goals of disarming Hamas and winning the return of all the hostages.

The line between “humanitarian aid” and “reconstruction” is also blurry. Do the humanitarian aid workers get decent housing and plumbing and trash pickup and, or do they live in desperation and squalor, too? Do schools resume classes? Who draws the lines and operates these services. The longer it goes on, with Israeli control of border crossings, the more it would appear that Israel is effectively occupying Gaza, only on a kind of remote-control basis. By refusing to distribute food aid, Hamas and its allies can generate a new “famine” for media consumption at will.

The Stephens-Schanzer approach also would probably take more time to achieve results than an invasion would—more time in which Israel is not at peace and in which its war aims in Gaza are unfulfilled. The New York Times has been complaining that Netanyahu has been prolonging the war for political reasons. Yet now that it looks like Netanyahu might move aggressively for a victory in Gaza, a prominent Times columnist advises an approach that would prolong the war? If it’s Israeli politics driving the war timeline (not a terrible thing in a democracy), maybe the Israeli public is ready for a rapid and decisive victory rather than more months of stop-start with uncertain results.

And the idea that Gazans are going to rise up against Hamas ignores that a lot of them have already been deeply indoctrinated by Hamas in their religious and educational institutions. There have been some hopeful developments in eastern Rafah (see “Gazans Are Finished With Hamas,” by Yasser Abu Shabab in the Wall Street Journal opinion pages, July 24). But, as with Ayatollah Khamenei in Iran, Hamas’s ruthlessness in maintaining its rule has outweighed U.S. and Israeli dexterity or fidelity in supporting its opponents.

I’m not cheering on a full invasion. But I don’t think the decision is at all as clear cut as does Stephens, who writes, “If Netanyahu makes the colossal mistake of trying to reoccupy Gaza for the long term, then no thoughtful person can be pro-Israel without also being against him.” (It’s a parallel to an earlier sentence in which Stephens writes, “No thoughtful person can be pro-Palestinian without also being anti-Hamas,” offering a Times readers a nice parallel between Hamas and Netanyahu. I don’t think Netanyahu is perfect or beyond criticism, but he has a better sense than anyone about what the Israeli electorate wants.

Absent from either the Schanzer or Stephens plan is another alternative, the one thing that would free the hostages faster than anything: America arresting the Hamas leaders in Qatar or Egypt and detaining them in Guantanamo as enemy combatants. “America to the rescue” has its own downsides for Israeli self-reliance, but from an American global leadership and deterring terrorism point of view, there are real advantages to that approach. The sooner it happens, the less likely it is that the Hamas leaders now living in luxury will disappear beyond the reach of justice.

Know someone who would enjoy or benefit from reading The Editors? Please help us grow by forwarding this email along with a suggestion that they subscribe. Or send a gift subscription:

I am with you on going faster in Gaza not slower. For all the reasons you present.

I have one question that has perplexed me from the start and that seems central to the way Israel has tied itself down in this long battle. The issue of the hostages. I keep thinking about Entebbe. However strong Israel's absolutism has been about always seeking to free a hostage, that did not preclude Israel from risking those hostages' lives as well in that gamble. Entebbe was masterful, but still three hostages died during it. It seems to me Israel has unnecessarily tied its hands with its absolutism on this issue. If a raid now could pull off rescuing a few, even if one or two died, it would break a terrible spell. Given the hideous condition Evyatar David appears to be in, how much longer can he survive anyway? I believe if I were him, at least a part of me would be thinking, "do it, now. It's worth the risk." This might break the hold Hamas has had over Israeli opinion, unsettle the world's horrible attitude, and convince Hamas to face facts and give up the ghost.

“But to understand what’s happening in America, you need to get beyond the academic economists and the legacy media journalists reliant on the academic economists, and watch some of the cultural signals.” I don’t even know where to start. There are so many places you could go to actually understand what’s happening with American manufacturing, and how much more complicated the impact of tariffs are than just “prices might go up a bit”- I dunno, talking to American manufacturers might be more helpful than a vibe check. It’s genuinely great that more people want to buy American made products, but if American manufacturers can’t profitably serve that market, that demand doesn’t matter.