Journalists Are “Self-Important, Pompous,” Washington Post Editor Concedes

Plus, Fed Chairman Powell on long-term growth; a Princeton club overreacts to a professor’s visit; Illinois spending surge; Harvard update

The former editor of the New York Times editorial page, James Bennet; the deputy opinion editor of the Washington Post, Charles Lane; a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, Thomas Chatterton Williams; and the editor in chief of the Washington Free Beacon, Eliana Johnson, got together Wednesday night for an event on “The New Illiberalism: The American Media and the Future of Democracy.”

A friend suggested that the American Enterprise Institute event was worth checking out, and he was right, even though I’d already read Bennet’s piece in the Economist on how The New York Times lost its way and wrote about it.

Bennet made working at the New York Times sound pretty terrible, asserting that “the Times had changed radically, culturally” during the ten years between when he’d been a reporter and when he returned to edit the editorial page. (Bennet was editing the Atlantic during that decade before Jeff Goldberg took over.) “The old rewards for being controversial, heterodox, challenging conventional wisdom,” had been “replaced by a desire to conform,” Bennet said. Inside the Times, he said, there was “a sense that you couldn’t publicly voice what you honestly think.”

Johnson said that when she talked recently to a Yale conservative student group, a substantial fraction of the students said they weren’t actually that conservative, they just “reject the monoculture on campus.” Johnson said the Free Beacon attracts some similar staff as reporters, and she said she explains to potential hires that the publication isn’t doctrinaire, beyond, “we are strident Zionists.” Lane quipped, “sounds like the old New Republic.”

Williams said readers might benefit from consuming a variety of news sources. He warned, though, that “that’s a lot to ask of a typical reader.”

“If you are tuned in to a variety of sources, you can kind of triangulate,” Williams said. “You can have a lot of value added by individual substacks.”

Johnson ridiculed what she called “the self-seriousness of the reporters, the idea that they think they’re neutral.”

Lane acknowledged that issue, with what I detected to be a bit of self-deprecating humor, but questioned how new it is. “It’s long been the case that journalists were self-important, pompous people,” he said.

Johnson said the liberal press, by avoiding certain topics, are “ceding huge ground to conservative media.” She offered as an example covering the Rockefeller and Ford foundations. “All you find is glowing profiles of the heads of these foundations,” she said. She also mentioned higher education. “I grew up in a household where it was highly valued to go to an Ivy League school,” she said. “I have no desire to fall over myself to get my kid into such an institution because I don’t think there’s a lot of value going on.”

Lane predicted there would be some continuing need for a press or some sort, so long as it can deliver on a basic mission: “People want to know what is going on.”

Powell on Marketplace: Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell recently sat for a discussion with Kai Ryssdal of the public radio show Marketplace. It was a long conversation, but my favorite part of it was this, from Powell: “You know, I think the things that really matter for our economy over the long term are not the Fed’s interest rate decisions, which really have no impact on the things that matter. .. The things that matter for the United States economy over the medium and longer term are not the decisions the Fed makes. The Fed tries to guide the economy to maximum employment and price stability through a business cycle and can react, we do critical things during crises. We’re very, very important in crises. But things that add to the productive capacity of the United States, things that give people more skills so they can contribute more to the economy, things that increase productivity so that an hour’s work is worth more output. That’s the evolution of technology. It’s also the skills that people have. Those things, investing in those things, that’s what drives the longer-run growth in the long-run economic well-being of our citizens, not the things that the Fed does.”

Some of that may just be buck-passing—hey, it’s not all the Fed’s fault if the economy and productivity aren’t growing. But a lot of it is totally worth remembering. The existence of the Fed doesn’t get mayors, governors, Congress, Treasury, or the president off the hook when it comes to tax, regulatory, trade, immigration, national security, health and education policies that maximize opportunity and create incentives for innovation and growth.

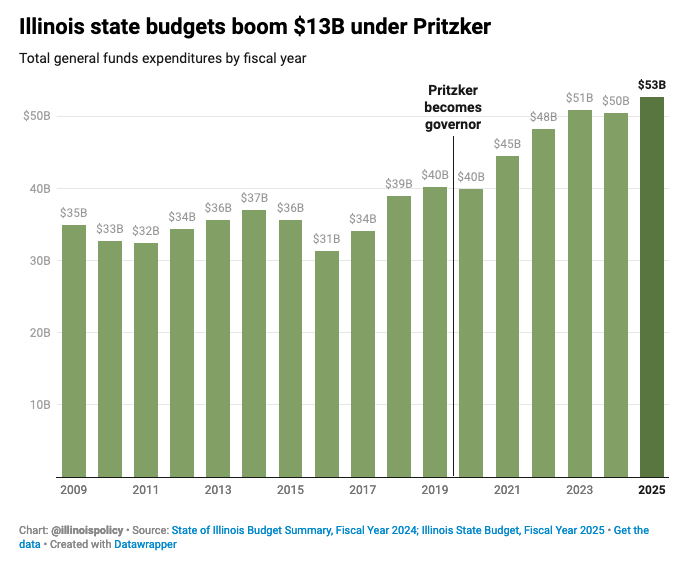

Prairie State spending soars: Illinois Policy, affiliated with the Illinois Policy Institute, has an article about Governor J.B. Pritzker’s 2025 budget, which includes a $93 million increase in state income taxes. At the Illinois state level, as at the federal level, the real budget story is the soaring spending.

The state’s population has been declining as businesses and talent take the “exit” ramp in the Albert Hirschman “Exit, Voice, and Loyalty” framework. (Ken Griffin moved to Florida.) So if the chart showed per-capita spending rather than total spending, the increase would be even more dramatic. Some of this money has been showered on states by the federal government, and a governor would have a hard time turning it down. But it’s also possible (at least in cases where no “maintenance of effort” rule or required matching applies) for a governor to use an influx of federal funds to ease off the tax pedal at the state level.

Recent work: “New York Times Imposes Its Own Anti-Israel Tilt on Pope’s Easter Message,” April 1, 2024, from the Algemeiner.

Harvard update: Lawrence Summers put out a series of tweets this morning faulting “Harvard’s leadership and its anti-semitism task force” for its so-far-anemic response to the Law School student government’s vote backing divestment from firms enabling Israel’s “genocide.” Said Summers, “I was very disappointed that the Harvard Law Student Government endorsed divesting in Israel. This following on what the Harvard Graduate Student Union did some time ago illustrates that there is a pervasive prejudice problem on the Harvard campus.” He went on, “I regret the failure of Harvard’s leadership and its anti-semitism task force to use this as a teachable moment. Efforts should be made to be in solidarity with Israeli students whose country is being vilified. And the question of why it is only the Jewish state called out for divestment in a world with much aggression and human rights abuse should be posed.”

Meanwhile, the Harvard Center for Middle Eastern Studies is set to host on April 18, 2024, Tareq Baconi, “president of the board, Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network,” who is just out with a New York Times article headlined “The Two-State Solution Is an Unjust, Impossible Fantasy.” The article uses the “apartheid” word three times, arguing instead for “A singe state from the river to the sea” [sic].

Princeton update: After a Princeton student brought his professor, Robert George, to lunch at the Charter club, the club took action, the student recounts in a column in the Daily Princetonian.

Charter’s president, Anna Johns ’25, announced an abrupt change to the club’s visitors policy. In order to maintain an “inclusive environment” and communicate that Charter is a “sanctuary” for its members, Johns wrote in a club-wide group chat, visitors who are not family members or friends would henceforth not be permitted to enter the club during its “hours of food service operations” without prior approval from undergraduate officers, club staff, and the alumni Board of Governors.

Within minutes following the announcement, I learned from friends that the policy had been crafted in direct response to student complaints about my Feb. 14 lunch with my professor. After seeking out the club manager, I learned more: A “group of membership” — whose identities and precise numbers were unspecified — felt “caught off guard” when they saw my professor in Charter, and they were deeply upset by his presence. In the future, at minimum, they wanted “the right to not be in that space” at the same time as him. After receiving their complaint, the club acceded to their demands.

While the club manager attempted to assure me that the new policy was viewpoint-neutral and not meant to single out any particular “belief systems,” claiming it was merely intended to further the value of “inclusivity,” she declined to affirm that my professor would be permitted to enter Charter’s premises in the future. The undergraduate officers, the alumni board, and club staff would have to consult with one another “to make sure it’s okay” — and, even in the event his entrance was approved, a “general consensus notice” would have to be sent out beforehand to all Charter members, warning them of the date and time the professor would be in the building so they would have the opportunity to stay away.

Professor George isn’t exactly my cup of tea—he’s a little too friendly with Cornel West for my taste—but the idea that to be “inclusive” a club has to basically ban conservative faculty members from dropping in as guests seems like a sad indicator of the state of certain campuses these days. The encouraging thing is that the student, Matthew Wilson, has a humdinger of a column about it, and that he managed to get it published in the Prince. It’s students like Wilson, with the sense to understand the difference between right and wrong, that are the best hope of improving these universities.

A regulatory double standard: A New York Times column by Jeff Sommer points out that advertising for state lotteries describes the jackpots in ways that overstates how much you could win. From the column:

Charles T. Clotfelter, a Duke economist who has studied lotteries for 50 years, told me that modern lotteries have been describing their prizes as “the numerical sum of years of payments” from the beginning. He added, “No one would let you state it in that form if it were a financial product.”

Jonathan D. Cohen, the author of “For a Dollar and a Dream: State Lotteries in Modern America,” said it was only in the 1980s and 1990s that lump-sum cash options — which reflect the real value of the prizes — began to be common.

“Lotteries are run by state agencies, and they’re exempt from truth in advertising laws,” he said. Indeed, I checked with federal agencies that deal with such matters, and was told that they have no jurisdiction over lotteries.

Not necessarily typical New York Times fare, but it resonated with me as an example of how sometimes government agencies can get away with things that are not allowed in the private sector.

More free-market New York Times news: Maybe the usual crew at the Times was off for the Easter holiday and a libertarian team from the Cato Institute or Reason magazine were filling in? Monday’s front page carries a lengthy feature by Roger Cohen about how unreasonable “environmental regulations” are strangling family farmers in France.

The Green Deal stipulates, for example, that hedges, home to nesting birds, cannot be cut between March 15 and the end of August. But in Isère, Ms. Chatelain said, no bird would nest in a hedge on March 15 because the hedge is still frozen.

Thierry Thenoz, 63, a pig farmer in Lescheroux in southeastern France, told me he had replanted miles of hedges on his 700-acre farm. “But if I want to cut a 25-foot break in the hedge for a gate and a track, I have to negotiate with regulators.”

A view from Columbia: The Times opinion sections, alas, seem to have the usual editors. One recent piece that I found particularly irksome came from a law professor at Columbua, Tim Wu, who “served on the National Economic Council as a special assistant to the president for competition and tech policy from 2021 to 2023.” Wu claims, “The Biden administration, in a break with center-left orthodoxy, seeks to address economic inequality not through taxation and transfers but through policies that allow more people and businesses to earn wealth in the first place.” That’s simply inaccurate; Biden is proposing a tax increase of $7 trillion, or $6 trillion more than Republicans want, to fund transfers such as increased spending on means-tested benefits for housing, child-care, and health care.

The Wu article goes on, “To succeed in the 2024 election, Mr. Biden needs to convince voters that he has begun a long fight against today’s toxic form of capitalism.” Maybe at Columbia law school or in New York Times opinion page headquarters a professor and his editors can convince themselves that the real secret to political success in 2024 will be conquering “today’s toxic form of capitalism.” But capitalism and free enterprise are fairly popular with American voters, who don’t generally consider them “toxic” but rather part of our economic system that creates opportunity and prosperity and protects property rights and economic freedom. Public opinion surveys show capitalism is more popular than Donald Trump, which may be why Biden is running against Trump rather than capitalism, and why Wu is back at Columbia and in the New York Times opinion pages rather than running Biden’s re-election campaign.

Thank you!: If you are enjoying this newsletter, please forward it to friends along with a recommendation that they subscribe. If you have feedback or ideas on how to make it better, get in touch: ira@futureofcapitalism.com.