Israel’s Value to U.S.: The Religious Dimension

An alternative to secularism.

Surveys showing some erosion of support for Israel, particularly among younger Americans, have fueled a boomlet of recent efforts to identify the benefits to the United States of the U.S.-Israel relationship.

In an interview with Elliot Kaufman of the Wall Street Journal, Israel’s ambassador to America, Yechiel Leiter, made a case for Israel based on geostrategy and military technology. Israel can be the leading force in the Middle East while the U.S focuses on China, and it can work with the U.S. on developing and producing missile defense that protects both Israel and the U.S. (In the same interview, Leiter tells Kaufman about Vice President Vance, “where it matters, I’ve only seen good and positive stuff. JD believes in America first, and I think he believes that part of America first is having a strong ally like Israel.”)

William McGurn followed up with a Wall Street Journal column praising Israel for offering an example of population growth fueling prosperity. “The Israelis have solved the problem of below-replacement fertility rates. In the Middle East and the wider world, Israel stands out for its healthy birthrate,” McGurn wrote.

The Hudson Institute’s Michael Doran published a column (“Tucker Carlson Claims Israel Is a Burden on the US. It Reveals Profound Strategic Ignorance”) offering some concrete examples of the benefits of U.S. security cooperation with Israel, describing it as “one of the engines of the American military’s strategic advantage in the 21st century.” He wrote about Israel’s use and modifications of the F-35 aircraft, of the Trophy system protecting tanks and armored personnel carriers, of the Lightening navigation pod, of a laser-based air-defense system, of an emergency bandage used by combat medics.

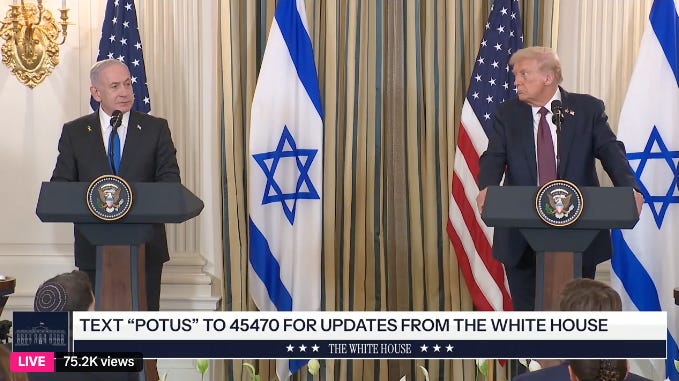

These are all worthy points, and I am glad they are being made. Yet on Christmas Eve and as Prime Minister Netanyahu prepares for another in-person meeting with President Trump, there is something to be said about Israel not only as a military, economic, and technological power, but as a society grounded in religious and spiritual and cultural identity.

Vance spoke about that, in relation to America, in a recent interview with Sohrab Ahmari at Unherd:

“When I talk about America having some common culture,” Vance says, “I think Christianity is very much at the heart of that. With the exception of Jefferson and a couple of others, most of our Founding Fathers were devout Christians. . . . There’s a lot about Christianity that is very useful, even if you’re not a Christian. I think Christianity gives us a common moral language. You saw that in the Civil Rights Era, you saw that during the Civil War. It was one of the ways that we were able to actually come together as a nation, post-Civil War: that shared Christian identity.”

Judaism’s function in Israel and Christianity’s function in America are different. Israel’s Declaration of Independence describes it as a Jewish State, while the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution says Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion. Yet there are nonetheless some parallels and common themes and shared history and culture and texts.

Look at Israel’s Declaration of Independence. It talks about how “The Land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people. Here their spiritual, religious and political identity was shaped. Here they first attained to statehood, created cultural values of national and universal significance and gave to the world the eternal Book of Books.” It talks about how the State of Israel “will be based on freedom, justice and peace as envisaged by the prophets of Israel” and how it “will ensure complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex; it will guarantee freedom of religion, conscience, language, education and culture; it will safeguard the Holy Places of all religions.”

Popes have talked about how Judaism and Christianity are in some ways sibling religions. Pope John Paul II, in April 1986, visited the Great Synagogue of Rome and said, “You are our dearly beloved brothers and, in a certain way, it could be said that you are our elder brothers.” When John Paul II visited Jerusalem in 2000, he left a note of prayer in the Western Wall: “we wish to commit ourselves to genuine brotherhood with the people of the Covenant.” Pope Francis, visiting the Rome synagogue in January 2016, used the word “brothers” seven times in a brief address. “You are our elder brothers and sisters,” Francis said.

It’s a controversial metaphor—Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, in his 1964 essay “Confrontation,” rejected it: “Nor are we related to any other faith community as ‘brethren.’” Soloveitchik, though, paradoxically concludes that “Confrontation” essay by turning to, all of things, a sibling metaphor: “Our representatives who meet with the spokesmen of the community of the many should be given instructions similar to those enunciated by our patriarch Jacob when he sent his agents to meet his brother Esau.”

As the mention of Jacob and Esau suggests, the sibling metaphor is not without complications. Neither Francis, nor John Paul II, nor Joseph B. Soloveitchik was an only child. They all had siblings. They must have been aware that “brotherhood” is a condition that involves not only love but also rivalry. Brothers and sisters compete for finite resources and parental affection. Even if these religious leaders hadn’t been familiar with that from personal experience, they’d be aware of it from literature, history, and the Bible. René Girard, a professor of French literature who taught at, among other places, Stanford and at Johns Hopkins, has written about what he calls “the basic mythical theme of enemy brothers.” Girard quotes Jeremiah 9:3: “Trust not even a brother, for every brother takes advantage.” And Girard also paraphrases the Harvard anthropologist Clyde Kluckhohn to the effect that “the most common of all mythical conflicts is the struggle between brothers, which generally ends in fratricide.”

A 2006 book by a professor at Hebrew University, Israel Jacob Yuval, “Two Nations in Your Womb : Perceptions of Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages,” formulates it this way: “The greater the consanguinity, the more intense the quarrel.” Yuval notes that Christians and Jews can’t even agree about which one is Jacob and which one is Esau. Jews see ourselves as blessed descendants of Jacob, while for Christians, “Esau was the archetype of the Jew, the elder brother who loses his birthright to the younger brother, the church.”

Jonathan Sacks, who was chief rabbi of Great Britain from 1991 to 2013, has a chapter about sibling rivalry in his 2015 book Not in God’s Name. “The first murder is a fratricide: Cain killing Abel,” Sacks writes. “The story of Hamlet begins with a fratricide.” Sacks goes on to mention that the founding myth of Rome is the story of Romulus killing his brother Remus. Sacks quotes a letter of Sigmund Freud: “The elder brother is the natural rival; the younger one feels for him an elemental, unfathomably deep hostility for which in later life the expressions ‘death wish’ and ‘murderous intent’ may be found appropriate.” Sacks then offers a plausible reading of Genesis supporting his contention that “Brothers need not conflict. Sibling rivalry is not fate but tragic error.”

Some of the hostility to Israel currently on display in parts of the Christian right seems animated by a focus on Jewish-Christian difference: the since-ousted Harvard Salient editor who privately proposed replacing Israel with a Palestinian state under “Christian custodianship”; the person who showed up at an October 29 Turning Point USA event at the University of Mississippi and asked Vance, “I’m a Christian man and I’m just confused why that there’s this notion that we might owe Israel something or that they’re our greatest ally or that we have to support this multi hundred billion dollar foreign aid package to Israel to cover this to quote Charlie Kirk ‘ethnic cleansing’ in Gaza. I’m just confused why this idea has come around considering the fact that not only does their religion not agree with ours but also openly supports the prosecution [sic] of ours.”

My own view is that the biggest threat to Christianity in the U.S. today isn’t Judaism, it’s secularism. Israel offers an alternative.

One could say that Saudi Arabia or Iran or Turkey also offer examples of religious states. Some see Islam as part of a trio with Judaism and Christianity of Abrahamic or monotheistic faiths. Yet what Israel offers that Saudi Arabia, Iran, and Turkey do not is a society that, however imperfectly, tries to combine individual freedom and autonomy and rule of law and democracy together with serious respect for and participation in vibrant religious tradition. It’s certainly not without a lot of tensions and frustrations and heated debate around everything from marriage officiation to public transportation on the Sabbath to whether fervently Orthodox yeshiva students should serve in the Army. I don’t want to make the error of overly romanticizing it or glossing over the imperfections. And there are certainly plenty of secular Israelis who contribute to the society in significant ways. Yet at best Israel’s Jewish keel, “the eternal Book of Books,” and the people that study and live it, have provided a sense of community, purpose, meaning, morality, and gratitude that have also characterized America at its best and that could today stand some additional strengthening.

Thank you: Merry Christmas to those celebrating the holiday. The Editors is a reader-supported publication that relies on paying customers to sustain its editorial independence. If you know someone who would enjoy or benefit from reading The Editors, please help us grow, and help your friends, family members, and associates understand the world around them, by forwarding this email along with a suggestion that they subscribe today. Or send a gift subscription. If it doesn’t work on mobile, try desktop. Or vice versa. Or ask a tech-savvy youngster to help. Thank you to those of who who have done this recently and thanks in advance to the rest of you.

The question of how Israel manages to keep up its fertility rate is an important one. It is not just because of large families among Haredi Jews or among Arabs. Even secular Jews have more kids than their counterparts in the diaspora.

One factor often considered as leading to smaller families is women working. But many women work in Israel.

Perhaps it is for the same reason as Jews had many children a century ago - the fear that some wouldn't survive. If that is the case, Arab attacks on Israel are not having the intended effect.