How “Big” Is the One Big Beautiful Bill?

Estimates of effect on deficit and debt differ vastly

How big is the “one big beautiful bill” passed by the House of Representatives this month? It seems like a question of fact, or simple arithmetic, but it turns out there is a wide range of estimates. The worst-case scenario is that over ten years it will add roughly $5 trillion to the federal debt, which is already at about $36 trillion. The best case scenario is that it will yield surpluses that reduce the debt by as much as $2 trillion. So the estimates differ by $7 trillion.

Let’s run down who is saying what, from the most optimistic to the most pessimistic, at least in terms of the debt effect. I found at least six different estimates.

The rosiest scenario comes from Peter Navarro, the White House senior counselor for trade and manufacturing, who has a Ph.D. in economics from Harvard. In a May 28 piece published in The Hill headlined “The bond market is missing the real ‘big, beautiful’ story,” Navarro contends, “the projected budget impact from the One Big Beautiful Bill Act ranges from a modest $300 billion increase in the debt under the 2.2 percent growth assumption to as much as a $2 trillion surplus under the 2.7 percent growth assumption.”

Another view comes from the center-right Tax Foundation, which found a ten-year conventional deficit increase of $2.5956 trillion and a ten-year dynamic deficit increase of $1.7007 trillion.

Another view comes from the Budget Lab at Yale, which finds, “The budget bill passed by the House on May 22 would add $2.4 trillion to the debt over the 2025-2034 window.” The Yale analysis is conventional, not dynamic, which is to say, “We thus do not account for any additional growth (or slowing of growth) that may emerge in the short or long run from passing this bill, nor do we analyze the impact of the increased debt burden on interest rates.” If you get into the fine print of the Yale analysis, though, it does concede that if you focus on “Provisions in Full Bill, as written, with Tariff Revenue,” the addition to the deficit for 2025-2034 is $1.770 trillion.

Another view comes from the Penn Wharton Budget Model, which finds a “conventional” cost of the bill at $2.787 trillion over ten years and a “dynamic” cost of it of $3.198 trillion.

Another view comes from the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, which cites a Congressional Budget Office estimate of $2.305 trillion more to the debt and then adds its own “interactions and post-score adjustments” to generate a total of $3.055 trillion.

The most negative view comes from, of all places, the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research, whose Jessica Riedl, a self-described “fiscal conservative,” cautions in a piece for MSNBC (“Trump's tax cut plan will be cripplingly expensive for most Americans”) that “the true 10-year tax cut cost likely approaches $6.5 trillion. The House bill would offset just $1.3 trillion with savings from programs such as Medicaid, SNAP and student loans — and the Senate is likely to strip many of those offsets.” She doesn’t give a precise number but based on her analysis I put it at roughly $5 trillion.

Who will be right? It will be hard to know in retrospect, because the decade could well include some other legislation with significant debt and deficit effects, or other events—a war, a pandemic, a financial crisis—that will make it difficult to isolate the budget effect of the One Big Beautiful Bill. So much of the forecast depends not on the law but on two variables—interest rates and GDP growth rate. If interest rates are lower, it affects the borrowing costs as the government rolls over existing debt, a lot of which was accumulated over the period of “ZIRP” or Zero Interest Rate Policy. And if GDP growth is higher, it means there is a bigger base of economic activity to tax, and less need to spend federal money on automatic stabilizers and welfare programs such as food stamps, extended unemployment benefits, Medicaid, or “stimulus.”

It’s a complicated communications challenge for Trump and his Republican Congressional allies. They want to emphasize the “big” part so that voters will be grateful for a large tax reduction, but they also want to downplay the “big” part so that the market doesn’t panic and create a debt crisis that spirals into a financial panic or even raises fears that make it harder and more expensive for the federal government to borrow money. The Navarro analysis depends on tariff revenues that may materialize or not depending on the outcomes of bilateral negotiations, U.S. litigation, and reshoring of manufacturing. The experience with Reagan and George H.W. Bush was that when it appeared that tax cut legislation was going to cause a big debt-deficit problem, Congress adjusted relatively quickly to try to address the issue.

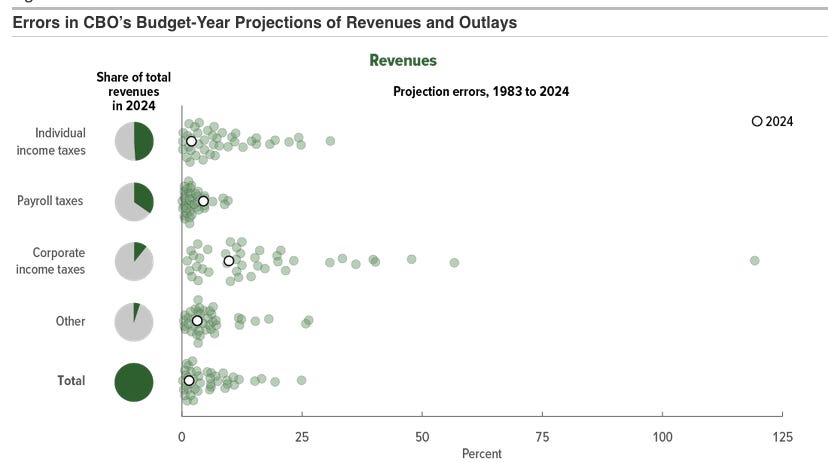

I’m not dismissive at all of the long-term debt and deficit risks, but my own view of it is the concerns of the deficit-debt hawks over the “one big beautiful bill” are somewhat overstated. If I had to pick one of these six estimates to bet on, it’d be the Tax Foundation’s dynamic estimate, not the Riedl-Manhattan Institute-MSNBC estimate. And if I had to pick an outlier to bet on, it’d be Navarro’s, not the Riedl-Manhattan Institute-MSNBC doomcast. Not that I am a big Navarro-tariff fan, but I think the GDP growth is likely to come in closer to 3 percent than two percent. Anyway, the fact that there are a range of estimates from a variety of sources is all the more reason not to elevate the Congressional Budget Office estimate over the other ones. CBO has a nice paper of how far off it is in predicting deficits and revenues on merely a year-ahead basis. Trying to make these estimates over a ten year period is an imprecise art, as the wide range of the forecasts indicates. And, as a political and practical matter, what the tax reductions (or, in the case of tariffs, increases) mean to individual taxpayers, businesses, and families may be more salient than what it means for the federal budget.

Recent work: The Wall Street Journal published a letter to the editor (“Has Donald Trump Done Higher Ed a Favor?”) I wrote about the federal government and Harvard. It’s the second letter linked at the headline. It also got some nice traction on X thanks to Jay Greene of the Heritage Foundation.

More recent work: “New York Times Lets Harvard Professor Whitewash University’s Jew-Hate” is the headline over my latest piece for the Algemeiner. It’s available at the Algemeiner website and also at the newish Algemeiner Substack, both of which have no paywall.

A more fundamental question is whether there should be "one big bill" or instead have votes on each component separately. We have moved towards big bills because they only require majority votes in the Senate, while most other bills require 60 votes,. Often, supporters have 50+ votes but lack 60, so many bills with majority support fail to get to the president's desk. The result is that recent presidents have pivoted to ruling by executive orders rather than laws.

This is not what the Founders intended.