Heritage Foundation Christian Touts “Tech-Free Sabbaths” at Harvard Conference

After neo-liberalism comes...a religious revival?

Instead of writing up and publishing immediately my account of the “After Neoliberalism: From Left to Right,” conference that happened Thursday and Friday in Harvard’s David Rubenstein Treehouse, I took a break from work to spend the sabbath with family and friends.

Stepping away from the computer before sunset Friday is my regular practice, but, as it turned out, I also was following the advice of some of the speakers at the conference. Emma Waters, a policy analyst at the Heritage Foundation who described herself as an evangelical Christian, called in her remarks at the event for “spiritual wellbeing” and “willingness to bring religion into the conversation.”

“Religion is the mother of ethics,” Waters said, encouraging attendees to follow the example of the children of Israel in the wilderness after leaving Egypt and “unlearn habits of servitude” by considering “tech-free sabbaths.” (Assassinated Republican activist Charlie Kirk’s posthumously published book, “Stop, in the Name of God: Why Honoring the Sabbath Will Transform Your Life,” released December 2, 2025, is the no. 2 bestselling book in the whole country on Amazon.) [Waters was the first person Heritage president Kevin Roberts called on in his November 5 town hall amid a furor over his defense of Tucker Carlson, at which Waters declared Roberts had the “godly character” to lead the organization and proceeded to voice her concern about the “betrayal of trust” posed by leaks to the press from Heritage.]

“I do think that our religious traditions are very important,” said a Princeton history professor, D. Graham Burnett, who spoke of the importance of “human values other than money values.”

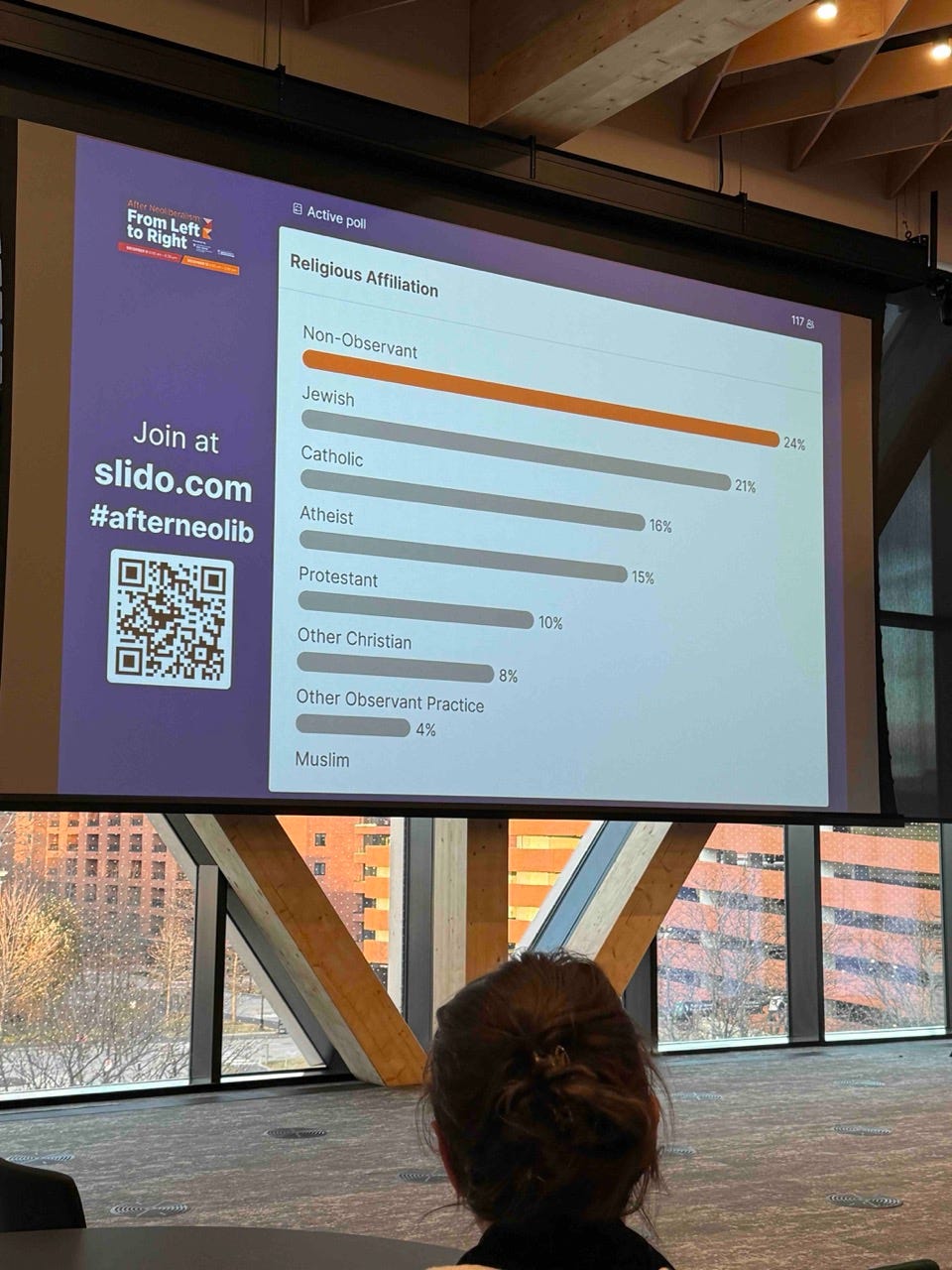

An online demographic poll conducted during the conference asked for religious affiliation. Of those who participated in the survey, “non-observant” was the top answer, with 24 percent, followed by Jewish at 21 percent, Catholic at 16 percent, and atheist at 15 percent. Yet that the question was asked and data were collected and reported about religion, rather than about other identity or diversity categories, sent a message that aligned with that of Waters and of Burnett.

For me the sabbath break turned out not to be harmful to my work but probably advantageous. It gave me some time to rest and recharge and also to think through what I saw and heard at the conference. What happened there has possible implications for the national political economy story and also for the related story about how Harvard is navigating and responding to the shifting political, economic, and cultural currents in the U.S.

The meeting wasn’t only academics, journalists, and think tank people. Even the Trump administration sent a representative. The chief economist of President Trump’s White House Council on Economic Advisers, Aaron Hedlund, told the Harvard audience Thursday that “trust in elites” is being replaced by “skepticism of elites.”

One reason the conference took me much of shabbat to process is that I had mixed reactions to it—both on the national political economy level and, relatedly, on the Harvard level. Mixed because while I appreciate the attention to religion and am in favor of most of the themes that Anne-Marie Slaughter mentioned as alternatives to neoliberalism—”human flourishing,” “well-being,” “community and place,” “national strength and cohesion”— I disagreed with some of what I heard being proposed as tactics toward those ends. Wrapping up the conference, the organizer, Danielle Allen, who is James Bryant Conant University Professor at Harvard and who was a candidate for the Democratic nomination for governor of Massachusetts in 2022, said neoliberalism—which she defined as trade liberalization, globalization, reliance on markets as solvers of problems with the aim of maximizing personal freedom and economic growth—”really is over because politics has gotten rid of it.” I agree with David Greenberg that the term neoliberalism isn’t useful. Also, and relatedly, many of the things that are being described as neoliberalism are not as “over” as the critics wish, and some of them were never as prevalent as their critics imagine. As Harvard economist Jason Furman pointed out in his remarks, lumping President Reagan, Clinton, and Obama into one bucket “makes relatively little sense.”

Some of the speakers just seemed unhappy. One moderator apologized for the weather in Boston—on a beautiful if brisk day, the sidewalks slush-free. Another speaker, making some point about phones and social media or, as he framed it, the monetization of “the deepest stuff of personhood,” declared, “that’s why we don’t feel good.” (This gloom, articulated as a shared illness, appears widespread in some circles. Senator Warnock, Democrat of Georgia, said at a separate December 11 Center for American Progress Event on “Healing America’s Spiritual Crisis,” “The whole country has what I call a lowgrade fever. You know when you wake up and something just doesn’t feel quite right. You can’t quite put your finger on it, but you know you don’t feel too good. An ache, a fogginess, and a fatigue that does not allow you to show up in your full strength to be your best self.” Speak for yourself, senator.)

If skepticism of elites is indeed on the rise, it may partly owe to elite failure to appreciate just how terrific a place America is right now, even with all its challenges. As an antidote in that category, one of my favorite takeaway lines from the two-day event came not from any Harvard professor or right-wing think-tank scholar, but from a left-leaning strategist, Rashad Robinson, who said there’s no time machine that he’d get into or bring black or gay people into. I understood it to mean that for a black gay social justice advocate, America in December 2025 is on a net basis, even with its imperfections and room for improvement, better than it’s ever been in the past.

Other speakers at the Harvard conference demonized the rich or pushed for policies to diminish their wealth and power.

“Right now, returns on capital are too high,” declared Matt Stoller of the American Economic Liberties Project, declaring that “Mark Zuckerberg has too much power” and “Meta is a destructive institution.” Stoller said he wanted to “definancialize our economy” and discussed taking away money from Zuckerberg: “It’s not his wealth, it’s our wealth.” Stoller is tall and has a full head of hair. I briefly considered approaching him in the hallway to ask how he’d feel if I said he had too much height and hair and should have to lose some of it for equality’s sake in the same way he was proposing to reduce Zuckerberg’s excessive share.

“I would like to see a wealth tax,” said a Harvard professor, Dani Rodrik, though he said he didn’t necessarily see it as a cure-all for the problem of “a crony capitalism that is increasingly authoritarian.”

“Wealth is not good. Wealth is corroding. Let’s make wealthy people the villains,” the Roosevelt Institute’s Felicia Wong said, though cautioning, that as a political matter, that message is problematic, because “many people want to be wealthy.”

My reaction to the conference in the Harvard context, as it was in the national policy context, is mixed.

One could say this was a pretty terrific event. A representative from the Trump administration showed up at Harvard and wasn’t interrupted by any protesters. A university criticized for its stifling ideological conformity is putting on its stage speakers from conservative think tanks including not only Heritage but also the American Enterprise Institute and the Manhattan Institute and the Ethics and Public Policy Center. There was even an evangelical Christian speaker who didn’t come from a New York or Washington think tank, but from Colorado. If Harvard is salvageable it’ll be because of professors like Danielle Allen.

One could say, too, that there’s something at least a little weird about having a half-million-dollar conference funded by the $13 billion William and Flora Hewlett Foundation in the David Rubenstein Treehouse (named after the UChicago board chairman who made a multi-billion-dollar fortune mainly with private equity investing at Carlyle Group) and inviting speakers to go on about “profiteering” and how it erodes trust to have hospitals owned by private equity. Maybe if returns on capital were as low as Matt Stoller says he wants them to be, Rubenstein wouldn’t have enough money to donate treehouses even to universities that compete with the one he chairs the board of, and Hewlett wouldn’t be flush enough to drop half a million on a Harvard conference.

At one point during the conference on Friday, someone got up and said his two children both went to Harvard until they dropped out to work on artificial intelligence models. Harvard can have conference after conference on definancializing the economy and on alternatives to “a world in which value is money value.” Yet for better or worse—and mostly for better—it and the rest of us still live in a world of strong market forces and portable talent. If and when Harvard starts putting on conferences and naming buildings on the basis of sabbath observance or “wellbeing” rather than cash on the barrel, and if and when its students start making career choices on those considerations in large numbers, it’ll be a sign of genuine traction for the “after neoliberalism” crowd. Until then, we are not “after,” but instead we are pretty much where modern America has always been—in a capitalist economy where the laws of economics apply, and one where people also value faith and family and community in ways that frequently are complementary with, not in conflict with, free markets and economic productivity. That is, a place where a reporter can take a break for shabbat and the article that comes out afterward winds up even better. And also a place where what matters, in the end, isn’t only the article but also its author’s relationships and flourishing.

Thank you: The Editors gets no support from the Hewlett Foundation. We are a reader-supported publication that relies on paying subscribers for our editorial independence. If you are a paying subscriber to The Editors already, thank you. For the rest of you, if you appreciate the content, please become a paying subscriber today to assure your full access and help support our independent journalism. The cost is as little as $1.54 a week, which is less than a cup of coffee.

“Wealth is not good. Wealth is corroding. Let’s make wealthy people the villains,” the Roosevelt Institute’s Felicia Wong said. Roosevelt is funded by the MacArthur Foundation, the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, Pivotal (Melinda French Gates) and others. Without wealthy people, Felicia Wong have to find another job. I'm also curious about her salary, benefits, and net worth.