Harvard Is Borrowing Money To Invest in Private Equity and Hedge Funds

Highlights from the “roadshow” for $450 million in new debt

If someone showed up at your door wanting to borrow $7 billion to invest in private equity and hedge funds, you might wonder about their recent track record.

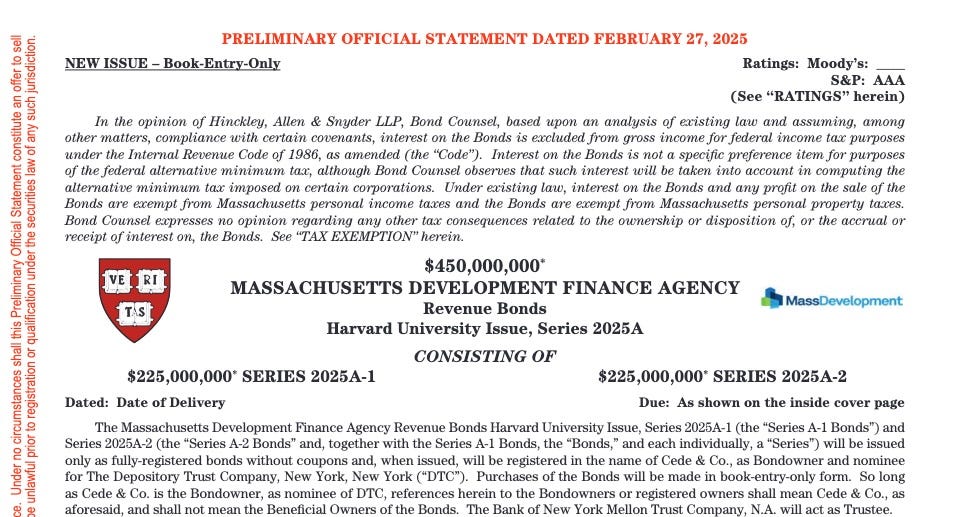

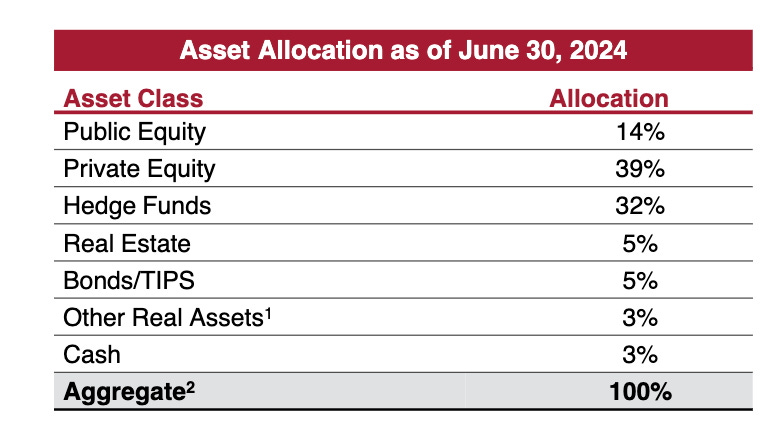

Here—obtained from the “roadshow” slides of the relevant borrower—are the asset allocation and the results, along with some commentary and analysis.

The borrower is Harvard, so the investment isn’t just to grow the principal but also to generate income for use to support research and teaching. Yet the four years from 2021 to 2024 look pretty flat during a stretch that for the S&P 500 showed healthy growth. Plenty of personal retirement accounts have done better than Harvard’s endowment during this period, including those managed by people who are not anyone’s idea of Warren Buffett. For the year ended June 30, 2024, Harvard reported a 9.6 percent annual return and the S&P 500 was up 24.6 percent. Janet Lorin at Bloomberg has been all over the Harvard endowment’s underperformance, and for good reason.

Harvard says it has $7.1 billion in debt and that this latest $450 million batch will be used “to finance and refinance certain capital projects…and to pay certain costs of issuance.” The “costs of issuance” include fees to bankers—Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley—and lawyers. Money is fungible, so if Harvard chose, it could borrow less and use up the endowment even more (or, perhaps better yet long-term, invest it even better). (Some endowment funds are legally restricted, but the basic point remains.) People will complain the headline is inaccurate—they’ll say the money isn’t being used to invest in hedge funds and private equity, but to pay for dorm renovations and a boathouse.

The boathouse is a good example. The bond offering documents say, “Specifically, the capital projects currently expected to be financed or refinanced, in whole or in part, with proceeds of the Bonds (the ‘Projects’) include renovations to undergraduate student housing at the main campus, renovations to teaching and administrative buildings at the main campus, renovations to research facility buildings in the main campus and the Longwood campus, and renovation of the Newell Boathouse building at the Allston campus.” Yet the Crimson reported in October 2024 that the Newell Boathouse renovations were “almost completed,” having begun in April 2023, and that the renovated boathouse had opened in February 2024. Why is Harvard borrowing money now to finance, or refinance, a boathouse renovation that happened last year? The answer is that the borrowing is only notionally to do with the boathouse—it’s really to make sure that Harvard didn’t have to exit any of the hedge fund or private equity investments to pay for that work on the boathouse.

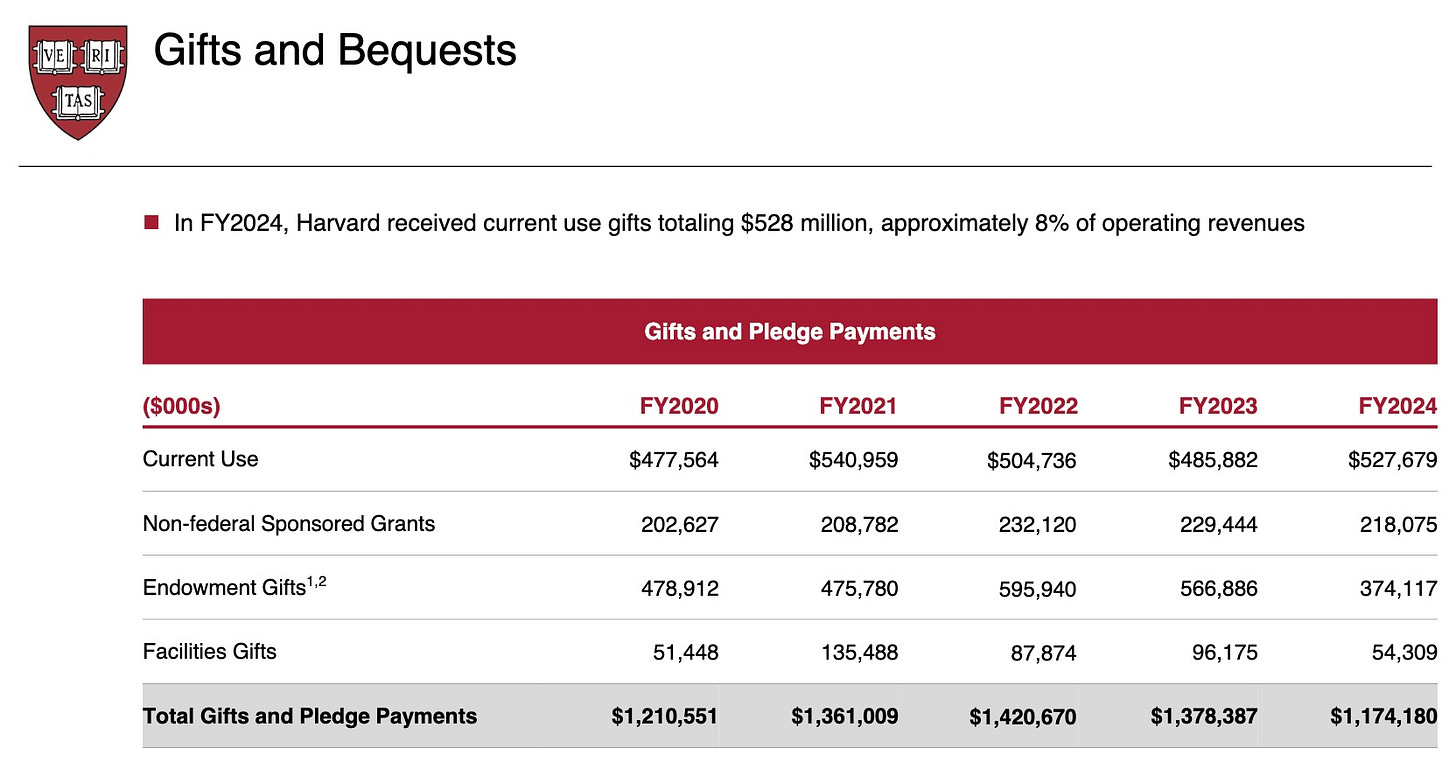

An option other than borrowing—get more from donors—appears less promising, or at least less realistic under current conditions. Here’s the slide on gifts and pledge payments.

It shows Harvard’s total “gift and pledge payments” down to $1.17 billion in fiscal 2024 from $1.38 billion in fiscal 2023, a decline of $204,207,000. Maybe donors are deciding against handing money to Harvard so that Harvard can then invest it in hedge funds and private equity. Can you blame them?

One backer not pulling the plug on Harvard: the state of Massachusetts. The $450 million in borrowing is via the Massachusetts Development Finance Agency and is therefore tax exempt at the state level.

The federal level may be dicier. Congress is eying increased taxes on university endowment distributions as part of the overall tax overhaul, and related to concern about an epidemic of Jew-hate on college campuses. The former Treasury Secretary, Larry Summers, who is also a former Harvard president and a current professor, posted to X last night that “Harvard continues its failure to effectively address antisemitism. Despite President Garber’s clear and strong personal moral commitment, he has lacked the will and/or leverage to effect the necessary large scale change, and the Corporation has been ineffectual.”

To be clear, I have nothing against private equity or hedge fund managers or even bankers in the municipal bond business. Paying their fees may have higher utility than some of Harvard’s investments in instruction. But at a certain point it all starts to feel a bit afield from the teaching and research mission, and, in the worst cases, to insulate the institution from the market forces that might otherwise provide some more accountability and guardrails.

A recent Grant’s Interest Rate Observer conference featured a presentation by Bill Ackman (a hedge fund manager himself) on shorting Harvard. If you could put on such a trade with borrowed tax-free money, it might be tempting. Maybe Harvard’s big Yale-style private equity payday will arrive someday soon, or maybe President Garber and the latest in the rotating parade of endowment managers will be gone before then.