Bernie Marcus

Harvard’s loss, and America’s win

My email inbox filled up this afternoon with messages from Jewish and right-of-center nonprofit organizations mourning the loss of Bernie Marcus, a founder of Home Depot and a significant philanthropist.

The national president of the Zionist Organization of America, Morton Klein, noted that Marcus had been honored at the group’s 2016 gala with the Justice Louis D. Brandeis Award. Klein described him as “an extraordinary Zionist, American patriot, business giant, philanthropic titan, devoted ZOA supporter and my dear friend.”

The Vandenberg Coalition, a bipartisan foreign policy group chaired by The Editors guest writer Elliott Abrams, put out a statement describing him as “a tireless champion of his home city, of the American Jewish community and the state of Israel, and of the principles of democracy, freedom, and community.”

The CEO of Tikvah, Eric Cohen, sent a note explaining that “Many of our most important initiatives, especially those focused on educating young Jews to understand and celebrate the history and heroes of the Jewish people and Jewish state, are only possible because of the seed funding and ongoing support provided by the Marcus Foundation.”

My own appreciation of Marcus relates less to his charitable giving, impressive though it has been, and more to three other dimensions.

I appreciate him as a customer of Home Depot, the company he helped to create. When I bought my first apartment in New York City in 2002, the kitchen needed renovating. I didn’t hire an architect or an interior decorator. I went to Home Depot, which helped me pick out and custom-order cabinets that fit the space. Since then, when I needed lumber, or power tools, or an appliance, or paint, Home Depot has frequently, if not always, been the place with the best combination of price and convenience, winning my business and helping to solve my problems in a highly competitive market. Home Depot’s success has come at some cost to other competitors, as I learned at some expense as a shareholder of one of them. But a lot of the time, they’ve got the best price and the fastest delivery time for whatever it is I need to buy. That’s the way free market capitalism is supposed to work—you make a big fortune by providing value to customers and earning their trust, not by ripping them off.

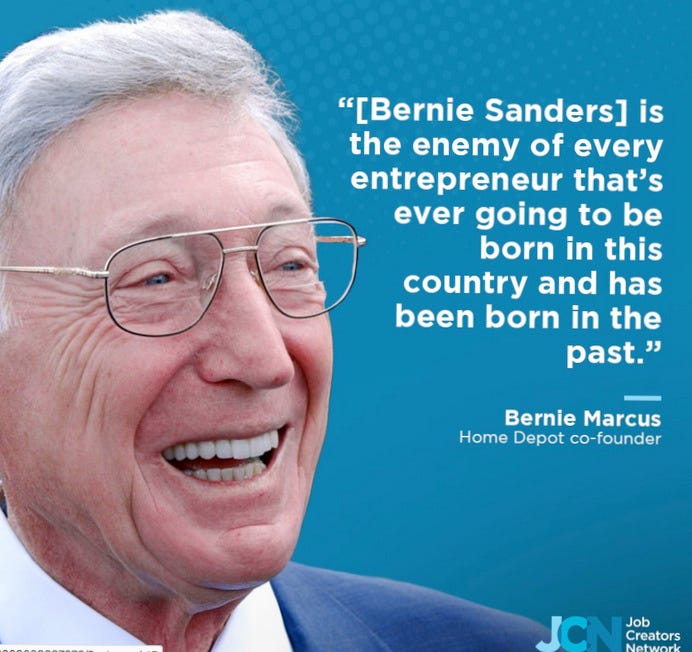

Perhaps relatedly, I appreciate Marcus as a spokesman for free enterprise. “Kick Up The Dust,” Marcus’s 2022 book, has a chapter titled “Capitalism Is Not a Dirty Word.” Wrote Marcus, “These days, building a profitable business is regarded as something evil. It’s like everyone believes that famous Balzac quote, the epigraph to The Godfather, ‘Behind every fortune there is a crime.’ But I have nothing to apologize for. I am the son of immigrants who fled the violence of eastern Europe and came through Ellis Island in the early twentieth century with nothing. I grew up poor and made it the old-fashioned way: I had bold plans, took big risks, and helped build one of America’s most iconic businesses.”

And third, and also relatedly, I appreciate Marcus as an example of American upward mobility. Bernie Marcus was “born on May 12, 1929, the youngest of four children of Sara and Joe Marcus, poor Russian immigrants in Newark, New Jersey. They lived in a fourth-floor walkup tenement,” is how the obituary posted to his Facebook page puts it. The son of a cabinetmaker and of an arthritis-afflicted garment worker who survived the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire, “he began working at age 11 to help support his family, with jobs including grocery store and candy store clerk, a theater usher, a magician and a hypnotist.” Not all the poor immigrants and their children are ruining our country. A lot of them have made it a better place. Some of them succeed in spectacular ways.

One final footnote for those readers who are here for the Harvard antisemitism coverage, which is a regular theme, and where we have had groundbreaking news. Bernie Marcus, according to the obituary posted on his Facebook page, was a victim of anti-Jewish bias at Harvard: “When he completed most of his pre-med courses at Rutgers University, he was told he had secured a scholarship to, and been accepted to, Harvard Medical School. His dream was not to be realized: a quota on Jewish students required an additional admission fee that was much more than his family could afford. He returned to Rutgers and graduated with a degree in pharmacy in 1954.”

As so often with the anti-Jewish discrimination, it was Harvard’s loss.

The right way to look at the Bernie Marcus story, though, is not through what it means for Harvard, but for what it means for America. And there the decision to offer refuge and entry via Ellis Island to Sara Schinofsky Marcus, born in Ukraine in 1896, and Joseph Marcus, born in Russia in 1889, was, without any question, one very big win.

Thank you: The editor of The Editors is himself a grandchild of an immigrant who came through Ellis Island. I have ambitions to follow in Bernie Marcus’s entrepreneurial footsteps by providing good value to customers. If you can afford the $8 a month or $80 a year to become a paying subscriber, please sign up today. Your subscription will ensure your continued full access to the content, sustain our editorial independence, and support our continued growth.

My father also suffered academic discrimination. Never a fine student, he was rejected from McGill because Jewish students needed a 10 point higher score to get in (high school grades were on a 100 point system).

Instead he went into the clothing business started by his father and uncle. Although he died at age 40, his first cousin Alvin Segal succeeded him as president of Peerless Clothing, and went on to create a highly successful business as described in the WSJ obituary for Alvin (https://www.wsj.com/articles/alvin-segal-made-peerless-a-giant-in-suits-and-sport-coats-11668784937; it was the 3rd partner, Larry Lovell, who threw the scissors). The months-long delay in the original NAFTA agreement over what called in public the "textile issue" was called by the negotiators "the Segal issue". Alvin was a big Trump supporter.

McGill's discrimination against Jews also had another effect: if you met a Jew at McGill, you knew that person had to be smarter than average to have gotten in. There are many good stories about Jews at McGill in those days in the book "Leonard Cohen, Untold Stories: The Early Years" (https://www.amazon.com/Leonard-Cohen-Untold-Stories-Early/dp/1982152621). In addition to Leonard Cohen, other notable characters are Ruth Wisse, my uncle Hersh Segal, and Boston pediatric neurologist Paul Rosman.

McGill discriminated, but they couldn't keep good people down.

Tnk u. Fine piece.